Problems with creation of complicated parts out of plastic which involve the integration of multiple materials are a typical issue resulting in the delay of production, excessive expenditure, and components that simply could not work as intended. This frustration may kill your projects and suck some of your profits, as you question whether there is a missing element in the puzzle. However, what would happen in case you had a roadmap to the key design strategies that would make this challenge a competitive edge?

The ability to design an overmolding and multi-material components requires a thorough knowledge of the material compatibility, bonding forces and particular molding principles. The success depends on the materials that are able to develop a robust chemical or mechanical bond. You should also come up with features such as good thickness of the walls, good interlocks, and positioning of gates. These are the basic rules that should be followed so that your final product can not only last long and be functional but also be pleasing to the eyes without making your manufacturing process very inefficient and costly.

It might sound like a lot to juggle, but breaking it down makes the process much more manageable. When I first started, I learned that a successful multi-material part isn’t just about the final product; it’s about making a series of smart decisions right from the very beginning. Each choice builds on the last, creating a strong foundation for a high-quality outcome.

So, where do we begin this journey? Let’s start with the most fundamental decision you’ll have to make, one that impacts every other step of the process.

What Are the Key Material Selection Criteria for Successful Overmolding?

Have you ever observed a product which has a soft-grip handle and begins to peel off of the hard-plastic body? This is a typical misalignment of materials, an error that may cost you to make an expensive recall and hurt the reputation of your brand. Selecting material is a daunting issue when there is a lot of choice. However, with some major criteria in mind, you can make the process easy, prevent such failures and have a solid bond with your parts.

The compatibility of materials is crucial to successful overmolding. You must select a substrate (rigid portion) and an overmold (soft portion) that can be bonded together. Chemical compatibility, processing temperatures and end requirements of final products should be your primary considerations. As an example, TPEs have good bonding with ABS and PC. More importantly, the melting point of the substrate should be more than the processing temperature of the overmold to ensure that the substrate does not suffer deformation during the second injection. This is the key to having a lasting component.

The bond between your two materials is everything. This bond can be either chemical or mechanical. A chemical bond is the ideal scenario where the two plastics fuse on a molecular level. This creates a very strong, seamless connection much like welding two pieces of metal. Unfortunately, this only occurs between specific families of plastics that are chemically compatible. If you can’t get a chemical bond, you have to make a mechanical one. This is where you design the part so the two materials are physically locked together. I’ve seen many projects succeed by focusing on one or both of these bonding types. To get you started, here is a simple table of common material pairings that are known to have good chemical adhesion:

| Substrate Material (Hard) | Compatible Overmold Material (Soft) | Bond Strength |

|---|---|---|

| ABS | TPE-S, TPU | Excellent |

| Polycarbonate (PC) | TPE-S, TPU | Good to Excellent |

| PC/ABS Alloy | TPE-S, TPU | Excellent |

| Nylon (PA6, PA66) | TPE-V, TPU | Good |

| Polypropylene (PP) | TPE-S (Special Grade), TPE-V | Good |

Beyond compatibility, you must consider the processing temperatures. The substrate is molded first and then transferred to a second cavity where the overmold material is injected onto it. If the incoming molten overmold material is hotter than the substrate’s melting point, it will deform or even melt the substrate, ruining the part. Always ensure the substrate has a higher heat resistance. This simple check can save you from a world of production headaches.

3 Designing to Overmold: 3 important things to keep in mind.

Compatibility and Mechanism of Bonding of Materials.

The most important and the first in overmolding design is the choice of material pairs which can create a stable bond. This attachment may be either chemical or mechanical or a mixture of the two. The chemically compatible pairs like TPE with ABS or PC can be fused together on a molecular level during the second shot which leads to the formation of excellent adhesion and durability.

In case of a weak chemical bonding or the absence of chemical bonding, the design should be based on mechanical interlocking like through-holes, undercuts, grooves, and texturing of surface to mechanically lock the overmold to the substrate.

Mathematically, in terms of tooling, the choice of materials also influences temperature of processing and mold construction. The substrate should not be deformed by high temperature and pressure during the second injection. CKMold frequently helps customers at this point by checking material combinations during DFM analysis and suggesting overmold-grade TPE, TPUs or specialty elastomers that are known to be compatible with familiar engineering plastics. Proper decision of the material at the early stage will avoid peeling, delamination and expensive field failures.

Part Geometry: Interlocks, Wall Thickness and Stress Control.

In case of an overmolded part, both materials with different stiffness and shrinkage rates interact with each other, creating complex thermal and mechanical stresses. These stresses need to be addressed by appropriate geometry design. Equal wall thickness of the substrate and the over mold layer incorporate equal cooling and minimizes warpage.

Radii are generous and smooth with well-defined shut-off edges that allow the structure to be structurally sound and ensures that there are no tears or sinks at the interface.

When there are peel or shear forces that are the most critical in load-bearing areas, mechanical interlocks ought to be employed. It has dovetail grooves, ribs and through-holes to enable the soft material to flow through and solidify forming anchor points that enhance bond strength dramatically. These interlock designs are directly refined in the mold cavity in CKMold overmolding projects, to provide repeatability and constant fill, even with high volume two-shot production.

Mold and Process design for overmolding: Gating, Alignment and Shot Sequencing.

A well-designed part might not be effective in the event the mold and the process are not programmed properly. Location at the gate should provide a flow of the substrate material and the overmold material that is smooth and balanced, and that would not leave any cosmetic defects and weak bonding areas. The former is frequently the first-shot gate, which is frequently buried behind the overmolding, whereas the second-shot gate should provide a uniform supply of material without pushing aside and damaging the substrate.

In two-shot molds, cavities have to be aligned. Index plates, rotating cores and part retention characteristics should contain tight tolerances so that the second material is always deposited in the right place. Accuracy of fixtures and repeatability of positioning is also important in insert or transfer overmolding. Here an expert mold manufacturer such CKMold can add value – to create mold structures, shut-off surfaces, and venting system, which assists in stable multi-material flow, high interfacial bonding, and production stability over the long-term.

When all three factors are considered in combination such as material compatibility, geometry with accurate interlocks and thickness control, and mold/process engineering, over-molding will become a controlled and predictable manufacturing operation, and not an experimental endeavor.

Selecting the Most Appropriate design for overmolding: Two-Shot, Insert or Secondary Overmolding.

The same process should not be used to make all of the multi-material parts. High volume parts which need to be accurately aligned and highly repeatable are best suited to two-shot molding whereas parts that need to incorporate metal or be pre-assembled with subparts are best suited to insert molding. Secondary overmolding, where the original component is hand moved into a second mold, is flexible in low-volume production, but presents the variability of alignment and labor.

The choice of process influences the cost of tooling, cycle time, level of automation and long run stability of production. These trade-offs will be understood early in the product design process to make sure the product design can be used in performance as well as scaled manufacturing.

Managing Interface Shrinkage, Warpage and Stress Dissimilar Materials.

The rate of shrinking and cooling different polymers varies and these variations may cause internal stress, warpage and bond failure in multi-material components. A hard substrate can hold back the contraction of a soft overmold resulting in peeling, distortion or surface sink.

To design materials and establish transition wall thickness, designers need to take into account coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE), crystallinity, and cooling behavior. There should be balanced cooling, appropriate location of the gate and homogeneous distribution of the material to avoid dimensional instability in the long run and early service failure.

How Do You Design Effective Mechanical Interlocks for a Secure Bond?

Relying on a chemical bond is a big risk, especially on parts that will be twisted, pulled, or put under constant stress. When that chemical bond fails, your product could literally fall apart in the user’s hands, raising serious safety concerns and damaging your brand. The idea of designing in a mechanical bond may sound like a complex proposition, but it doesn’t have to be that way. By adding a few simple, well-placed features, you can create a failsafe physical connection that adds incredible strength and reliability.

**Designing mechanical interlocks requires you to add physical features to the substrate for the overmold material to grab onto. You can do this by adding grooves, raised ribs, or through-holes into which the second material can flow and then solidify inside. These features serve almost like small anchors, physically locking the two materials together. Such a method is necessary when materials cannot bond chemically, such as TPE on polypropylene, in order to ensure a strong attachment without peeling or separating when a force is applied.

Think of a mechanical interlock as creating a puzzle-piece fit between your two materials. Instead of just relying on the materials to "stick" together, you’re making it physically impossible for them to separate without breaking. I remember a project for a client making durable handles for outdoor equipment. The materials they chose didn’t have a strong chemical bond, so we had to get creative. We designed the hard plastic core with a series of deep grooves and several holes that went all the way through the handle. When we injected the soft, grippy overmold material, it flowed into these grooves and through the holes, forming rivet-like structures once it cooled. The final product was incredibly strong; you simply could not tear the two materials apart.

Let’s break down some of the most effective types of mechanical interlocks:

- Through-Holes: These are holes that pass completely through the substrate. The overmold material flows through them, creating a solid "rivet" of material that locks the overmold on both sides. This is one of the strongest methods.

- Grooves and Channels: These are recessed areas on the substrate’s surface. A simple undercut or a dovetail-shaped groove can provide a very strong grip for the overmold material to latch onto.

- Textured Surfaces: For a less aggressive but still effective approach, you can design the substrate with a rough, textured surface. This increases the surface area for the overmold to adhere to and provides thousands of tiny anchor points.

The key is to place these features strategically in areas where the most force will be applied. By designing these interlocks into your part from the start, you ensure a durable product that will stand up to real-world use.

Molding Design Requirements of Reliable Overmolding and Multi-Material Production.

It is not only part design that determines successful overmolding, but also fine construction of the mold. The major ones would be the proper alignment of cavity between shots, strong part locating additions, regulated shut-off surfaces, and proper ventilation to prevent air traps in the bond interface. Two-shot molds require rotating cores or index plates to provide repeatability on the bonding level and appearance on a micron scale.

In the case of insert or transfer overmolding, not only the design, but also the placement of the fixtures has a direct impact on cosmetic finish and bond quality. Expenses on tooling modifications are minimized by early coordination of product designers and mold engineers, providing a stable mass production.

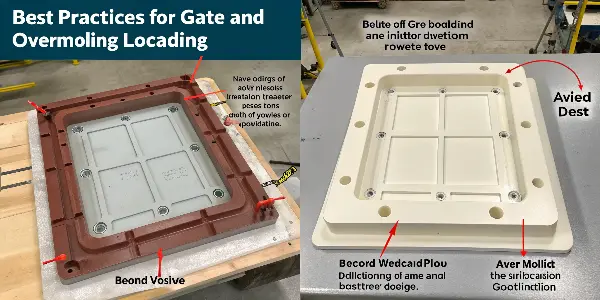

What Are the Best Practices for Gate Design and Location in Design for Overmolding?

Have you ever taken delivery on a batch of parts, only to find ugly flow marks right on a cosmetic surface, or found that the overmold is peeling off in one corner? These are often symptoms of poor gate design. A badly placed gate can cause a host of problems-from visual defects to weak bonds-leading to high scrap rates and missed deadlines. Figuring out where to put the gate can feel like a guessing game, but it’s not. By applying a few proven principles, you can control the material flow precisely and ensure a high-quality part every time.

For overmolding, gate placement is different for the two shots. For the first shot, or substrate, the gating should be in a non-visual area and designed so it will not warp the part. The second shot, or overmold, must be gated to allow the material to flow across the substrate without generating too much pressure that could dislodge it or cause cosmetic damage. It also needs to be placed away from cosmetically sensitive areas to avoid blemishes. Strategic gating helps create a strong bond with a flawless finish.

Gate design is one of those details that can make or break your project. I learned this the hard way in my early days. We were working on a consumer electronic device with a soft-touch TPE frame around a hard PC housing. Our initial gate for the TPE was too small and placed at one end of a long, thin section. Consequently, the TPE would cool down too much before it filled the entire frame, leading to weak spots and an incomplete bond on the far end. We had to rework the mold to add a second gate and widen the runners. It was an expensive lesson in the physics of polymer flow.

To avoid these problems, here are some key best practices for gating your overmolded parts:

- Gate the Substrate First: Place the gate for the rigid substrate in a location that will be covered by the overmold material. This hides any potential gate blemishes. Also, gate into the thickest section of the part to ensure uniform filling and minimize the risk of warpage.

- Protect the Substrate: The gate for the second shot should not inject molten plastic directly onto a delicate or thin area of the substrate. This high-pressure flow could cause erosion, breakage, or push the substrate out of position within the mold. Instead, aim the flow at a solid, robust part of the substrate.

- Ensure Even Flow: For the overmold, especially on long or complex shapes, consider using multiple gates or a fan gate. This helps the material spread out evenly and reduces the pressure needed to fill the cavity. This is crucial for maintaining a consistent overmold thickness and a strong, uniform bond.

- Hide the Overmold Gate: Just like with the substrate, try to position the overmold gate in a less visible area to maintain a clean, aesthetic appearance on the final product.

Proper gating isn’t just about getting plastic into the mold; it’s about controlling how it gets there. Taking the time to plan your gate locations with your mold maker will pay off with lower scrap rates and a better-looking, better-performing product.

How Do You Manage Wall Thickness and Transitions in Multi-Material Design?

One of the biggest design challenges in overmolding is managing the thickness of your materials. If the substrate walls are too thin, they can break during the second injection. If the layer of overmold is uneven, you get weak spots and cosmetic defects. Getting these transitions wrong leads to parts that fail quality control and waste time and money. Sometimes it may seem tricky to balance structural needs with a sleek design. But by following some very simple rules about wall thickness, you can make sure your parts are strong and beautiful.

In multi-material design, whenever possible, keep the substrate and overmold wall thickness consistent. A typical recommendation for overmold thickness is between 1.5mm and 3mm. Eliminate sharp corners and abrupt thickness transitions; instead use generous radii and provide smooth, transitional areas between thick and thin sections to avoid stress concentrations. Use consistent material flow to reduce the risk of some common molding defects, such as sink marks and voids, in order to create a more robust and reliable part.

I always tell my clients to think of molten plastic like water flowing through a river. Water flows best through a smooth, wide channel. If it hits a sharp corner or a sudden narrow spot, it creates turbulence. Molten plastic behaves in a very similar way. Abrupt changes in wall thickness create turbulence in the material flow, which can lead to a whole range of problems. You can get air traps, weak weld lines where two flow fronts meet, or sink marks on the surface as thicker sections cool and shrink more than thinner ones.

Let’s look at how to apply these rules in practice:

- Uniformity is Key: For the substrate, design it with a consistent wall thickness. This is a fundamental rule for all injection molding, but it’s especially critical here because this part has to withstand the pressure of the second shot.

- Define Overmold Thickness: The thickness of your soft overmold layer is also important. If it is too thin (less than 1mm), it can be difficult to fill and may peel off easily. If it is too thick, it can be prone to sinking and wastes material. A good range to aim for is typically between 1.5mm and 3mm.

- Smooth Everything Out: Where the overmold meets the substrate, you need a clean, well-defined shut-off line. Avoid feathering the edge of the overmold to zero thickness. This creates a fragile, paper-thin edge that will tear and peel away. Instead, design a groove or a step in the substrate for the overmold to terminate into. This defines a crisp, durable edge.

- Use Radii Generously: Banish sharp internal corners from your design. They concentrate stress and are prime spots for cracks to form. Always add a radius to both internal and external corners. A good rule of thumb is to make the internal radius at least 0.5 times the wall thickness.

By designing with smooth flow in mind, you are working with the molding process, not against it. This simple shift in thinking leads to better parts, fewer defects, and a much smoother production run.

Conclusion

Mastering the design of overmolded and multi-material parts comes down to a few key items: compatible materials, strong bonds both chemically and mechanically, molding process control via smart gating, and designing for manufacturability with uniform walls and smooth transitions. Paying attention to these key areas can take a very complex manufacturing challenge and distill it into a powerful tool for creating innovative, high-quality products that really set themselves apart in the marketplace.