Cosmetic imperfections such as eject pin marks is an all-too-common problem that can bring production to a standstill and undermine your bottom line. Think of the stress of being faced with a project delay of this magnitude and how it might be caused by something as minute as a few pesky marks. This is how we helped a client in the auto industry.

For addressing the serious issue of ejector pin marks for our car customer, we performed a thorough analysis on the topic with emphasis on three major aspects: design of the mold, parameters during the mold-making process, and material. The plan included redesigning the ejector pins for balanced force application, optimizing the pressure level and cooling time for minimizing internal stress components, and validating the flow properties of the material grade. The integrated strategy was must for removing the flaws at their roots so that flawless finish quality is attained.

On paper, the solution might seem simple, but it took a thorough and systematic investigation to arrive at that conclusion. Every component of the process, from the steel of the mold to the cooling water’s temperature, is suspect when a part fails. It’s never enough to blame the machine operator alone. Understanding the intricate interactions between design, material, and process is the true answer. Let’s now go over the precise actions we took to make this project a huge success rather than a possible failure.

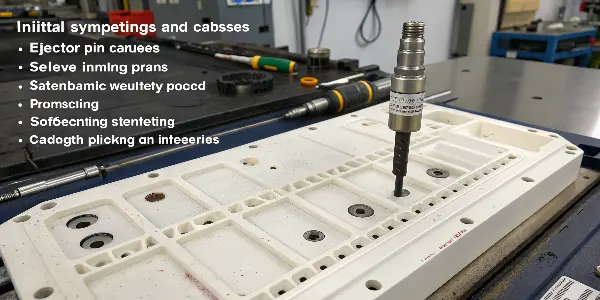

What Were the Initial Symptoms and Root Causes of the Ejector Pin Marks?

Everything looked great in the mold, but then you see them, the white stress patterns or the shiny spots where the ejector pins touched. You try tweaking the process, adjusting the settings, increasing or decreasing the pressure, hoping for the best, but the result is always the same. This is the same predicament our client found themselves in until they contacted us.

The first symptom observed was a severe whitening effect, along with slight indentations, in a large cosmetic panel made of ABS, which housed several ejector pin sites. Through our Root Cause Analysis, it was found that a number of issues cumulated: excessive pressure of the packings, inadequate cooling time, and a substandard ejector pin layout. This was because the pins then in use were of a size that was much smaller than required and were placed in thin-walled areas.

As soon as we received the sample component, we could recognize the problem at once. The component in question is the dashboard piece, which is a substantial component, an A-surface component, meaning its cosmetic finish is important. Although small, the defect is not acceptable in any automotive interior component. The company is at a point where they have a deadline to finish production. They are receiving immense pressure from their customer, who is a major automaker. They had been trying to vary their process parameters, but in vain, which is often a testimony in itself to the fact that there is possibly more to this than just a machine-related problem.

The Part Design and Material Choice

First, we examined the part’s geometry. The dashboard included both large, flat surfaces and complex features with varying wall thicknesses. The most severe ejector pin marks appeared where a thin wall transitioned to a thicker rib. This is a frequent source of conflict. The thicker sections cool more slowly than the thinner sections, resulting in uneven shrinkage and internal stress. When the ejector pins pushed against these stressed, thin areas, the material became easily blemished. The material, a standard grade of ABS, was appropriate for the application. However, its unique flow and shrinkage characteristics had to be considered in both mold design and process settings.

The Original Molding Process IN Ejector Pin Marks

Next, we investigated the client’s molding parameters. They applied high injection and packing pressures to ensure that the large part was completely filled. However, the high pressure forced the material hard against the mold walls, causing significant internal stress. At the same time, to meet cycle time targets, the cooling time was kept to a minimum. This meant that the part was still soft and hot when the ejection process began.

| Parameter | Original Setting | Our Recommended Setting |

|---|---|---|

| Packing Pressure | 110 MPa | 75 MPa |

| Cooling Time | 25 seconds | 40 seconds |

| Ejection Speed | High | Slow-Fast-Slow Profile |

| Melt Temperature | 240°C | 230°C |

Pushing a hot, highly stressed part out of the mold with small pins is a recipe for defects. The combination of these aggressive parameters was a primary contributor to the whitening and indentations.

The Flawed Ejector System

Finally, we examined the mold’s ejection system. The original design used about 20 small-diameter (6mm) ejector pins scattered across the part. Critically, several of these pins were located directly on the thinnest sections of the cosmetic surface. This design failed to properly distribute the force required to push the large part out of the core. All that force was concentrated on a few tiny points, exceeding the compressive strength of the warm plastic and leaving a permanent mark. It was clear that a comprehensive solution addressing all three areas was necessary.

What Effect did Draft and Wall Thickness Transitions Have in Forming the Defects?

Further examination showed that the marks of ejectors pins were not randomly distributed. They always seemed to be located at the wall thickness transitions, at the points where the thin cosmetic surfaces collided with the thicker ribs or structural elements. These shifts were not uniform and formed internal stress locally. These stressed areas were much susceptible to whitening and indention when ejection started taking place.

The angle of draft made the matter even worse. Draft was actually there in some of the affected regions, but it was not large enough to work on the material or the parts. This made the part hold onto the core more than anticipated, making the part ejection difficult. Rather than slide off the part, the part did not slide until the ejector pins exerted too much localized force.

This was a combination of uneven cooling due to thickness transfers and marginal draft that implied that the material could not be gradually forced out of the mold. The ejector pins were made the weakest point which revealed stress which was already enclosed in the part. To correct ejector pin marks could not be achieved merely by improved ejection equipment, but by a geometrical and material conscious awareness of the geometry, material behavior and release mechanics near the end of each molding cycle.

What Impacted Ejector Pin Marks on Production Cost, Scrap rate and Timelines of Deliveries?

Ejector pin marks were not merely a cosmetic flaw, prior to corrective action, they represented a direct business risk. The auto part used was an interior A-surface part, i.e., any slight areas of whitening or indents would be rejected automatically. The scrap rate rose sharply and became unacceptably high during the initial production trials. Every rejected component was a wasted material, machine time and labor which increased per-unit cost.

What was more problematic, uneven quality interfered with the production planning. Operators had to reduce cycles, pause machinery to make alterations and do inspections over and over. These disruptions led to missed milestone of deliveries, which strained the supplier as well as the OEM program schedule. Delays during this phase in automotive projects may be transferred to assembly-line time managerial problems and contractual fines.

What was worse about the situation was that the defect was intermittent. There were those parts that have passed inspection and those that had failed making it an element of uncertainty and loss of confidence in the stability of the process. Such inconsistency did not allow the client to increase the volumes of production, which effectively inhibited the approval of mass production.

The ejector pin marks were no longer a surface problem but a bottleneck in terms of cost control, delivery reliability and customer confidence. The resolution of the issue was critical to quality, as well as the ability to regain scalable and predictable production.

Why Process Parameter Adjustments Previously did not Work Before Mold Redesign Was adopted.

First, the client was trying to resolve the problem by modifying the parameters of the molding. Pressure in packing was minimized and cooling time was extended slightly and speed of ejection was adjusted. These changes brought about slight improvement, but still could not remove ejector pin marks in all occasions. This is typical of injection molding: even process tuning is unable to counteract a mechanically unstable mold completely.

The underlying cause was that the force necessary to eject the part was too much to allow small, poorly located pins to act upon unless they damaged the surface. Although pressure was decreased and time to cool was increased, the part stuck well on the core because of geometry and stress distribution. Consequently, ejector pins still focused the force on thin cosmetic regions.

The parameters of the process determine the amount of force required, but the shape of the mould determines the manner in which the force is distributed. The process window was very narrow without redistributing the load to the ejection system to make it a more balanced process. Any slight change in temperature, pressure, or material behavior brought about defects to reoccur. It was evident in this case that process optimization is most effective in cases where it is constructed on a sound mechanically sound design of the mold and not as an alternative to that.

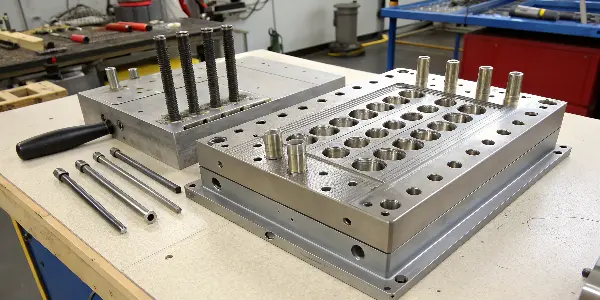

How Did We Redesign the Mold’s Ejection System for a Flawless Finish?

You picked up on the ejection system as the culprit, but the idea of overhauling the mold significantly intimidates me. Nobody’s got time for re-tooling when there are deadlines looming. The idea of re-designing a component of the mold sounds daunting, but with the right design, change can be a radical success without undertaking the whole project over. We realized simply adding more of these pins was not the way to go.

Secondly, we were able to redesign the ejection system of the mold by increasing the number of ejector pins from 20 to 32. This was done by placing them in rib, boss sections which are not cosmetic. Importantly, we used sleeve ejectors of higher diameter for critical areas around cosmetic surfaces instead of regular pins. This ensured that the pressure exerted by ejection was exerted over a broader area, reducing pressure per square inch to prevent deformation.

Our philosophy is to solve the problem at its mechanical source. While process adjustments can help, a fundamentally flawed mold design will always be a struggle. The goal of our redesign was simple: spread the load. Think of it like this: pushing a car with one finger will dent the panel, but pushing with your entire body against the frame will move it without damage. The same principle applies to ejecting a plastic part. We needed to replace the "fingertips" (small pins) with "open palms" (larger surfaces) to push the part out gently and evenly.

Strategic Pin Placement

The first step was a thorough re-evaluation of each ejector pin location. Using the part’s 3D model, we identified strong areas that could withstand the ejection force without causing any cosmetic damage. This entailed moving pins away from large, flat A-surfaces and toward the backside of ribs, the base of mounting bosses, and other structural elements. This alone made a big difference. We increased the number of pins not only to increase force, but also to ensure that the part was pushed out evenly, preventing twisting or binding in the mold, which can result in stress marks.

Introducing Ejector Sleeves and Blades

For areas where we absolutely had to place an ejector near a cosmetic surface, we changed the type of ejector. Instead of standard round pins, we used two other solutions:

- Ejector Sleeves: These are hollow pins that push on the circular boss around a screw hole. They eject on a ring of plastic, not a single point, spreading the force beautifully over a feature that is already structural. We used these on all the mounting bosses.

- Ejector Blades: For long, straight ribs, we replaced multiple small round pins with a single, rectangular blade ejector. This pushed along the entire length of the rib, providing stable and distributed force.

Balancing the Ejector Plate

Finally, we ensured the entire ejector plate assembly was perfectly balanced. An unbalanced system, where some pins engage before others, can cause the part to warp during ejection. We re-calculated the layout to ensure a uniform push across the entire surface. This redesign required precise CNC machining to modify the existing mold, but it was a targeted surgical strike, not a complete rebuild. This new, robust system was designed to work with the part, not against it, creating the foundation for a flawless finish.

What Optimized Process Parameters Were Key to Eliminating the Defects?

You’ve got a newly modified mold in hand, but you’re not through with the process yet. Installing the molding in the press with the old values in place will be like installing sports tires in your car, which you will never bother to balance. This will not provide you with the results you’re seeking. The mold and the molding process both represent two sides of the same coin.

Optimization of process parameters also proved very critical. We reduced the packing pressure considerably to reduce stress in the material and increased the cooling time by 15 seconds, ensuring the material had a good degree of hardness before removal. In addition, a multi-profile for removal, slow-fast-slow, was incorporated to reduce the material’s adhesion to the core before the application of the final pushing force. Raising the temperature of the melt slightly enhanced the material’s integrity and reduced the risk of stress whitening.

With the mechanically superior ejector system in place, we were able to develop a much gentler process for the part. We were no longer battling a bad design with brute force (high pressure). Instead, we could fine-tune the parameters to improve both quality and efficiency. I always tell my clients that a great mold simplifies the processor’s job. Our goal was to create a large, stable processing window that would allow them to consistently produce high-quality parts shift after shift.

Reducing Internal Stress

One cosmetic part’s number one enemy is internal stress. It’s an invisible force locked within the plastic that’s just waiting for an opportunity-like an ejector pin-to reveal itself as a blemish.

- Lower Packing Pressure: The original high packing pressure was a brute-force method to prevent sink marks. However, it also crammed too much material into the cavity, creating immense stress. With better gate locations and a balanced mold, we could lower this pressure significantly. The part was now "relaxed" rather than "stressed" as it cooled.

- Optimised Melt and Mold Temperature: We reduced the melt temperature slightly. A cooler melt is more viscous and less likely to become over-packed. Also, we cleaned up cooling channels in the mold for efficiency in cooling the part uniformly. Nonuniform cooling is one of the biggest causes of warpage and stress.

Ensuring Part Rigidity

The second key was making sure the part was solid enough to withstand ejection.

- Increased Cooling Time: The most impactful change was adding 15 seconds to the cooling time. This was a tough sell for a client focused on cycle time, but we proved it was essential. This extra time allowed the part to cool below its heat deflection temperature, making it far more rigid and resistant to indentation from the pins. In the end, eliminating rejects saved far more time and money than the slightly longer cycle.

Finessing the Ejection Sequence

Finally, we perfected the ejection. Rather than one strong push, they now involve a sequence of intelligent actions.

- Multi-Stage Ejection:

The sequence was:- Slow initial movement: The pins moved 1-2mm very slowly. This caused a gentle breakdown in the vacuum seal between the plastic component and the steel mold core.

- Fast main stroke: After the ejector is loosened, the ejectors rapidly pushed the part out from the mold.

- Slow final return: The pins were retracted slowly to avoid any slam or vibration in the mold.

The perfect blend of stress-free part, sufficient rigidity, and gentle ejection sequence offered by mold redesign became the ultimate solution that eliminated ejector pin marks totally.

Conclusion

We were able to successfully resolve our automotive client’s severe ejector pin mark issue by taking a holistic approach. The solution involved a systematic combination of redesigning the mold’s ejector system, optimizing the injection molding process parameters, and ensuring proper material handling. This case study exemplifies our dedication to digging deep to find the root cause of a problem, ensuring that our clients can consistently and confidently produce high-quality components.