Designing plastic parts that have complex characteristics such as a side hole or a locking clip feel amazing. Parting a normal two part mold can only be able to release these undercut features by entrapping or fracturing the part. This pushes you to a side where you either give in to compromise of your design or endure nightmare in manufacturing of damaged components, broken molds and expensive delays. But yet there is a graceful mode of solution which renders these complicated designs possible.

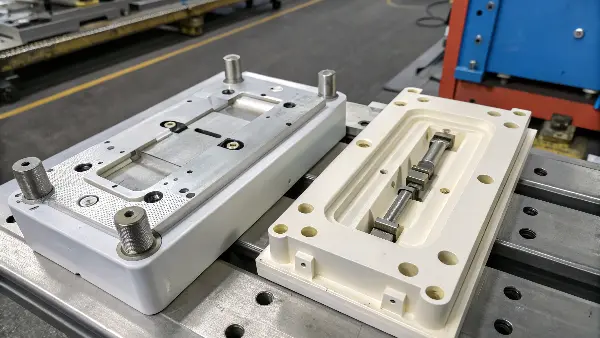

A slider or slide or lifter is a moving part of an injection mold that forms undercuts on a plastic component. It is designed to be inserted in place as the mold is closed and then pulled out horizontally after which the part can be ejected. This motion is usually created by a pin which should be angled to turn the motion of a vertical opening on the mold into the perpendicular motion of the slider where the part of the complex geometry is freed without any damage or hindrance.

Understanding this basic principle is the first step, and it’s a big one. It opens up a whole new world of possibilities for your part designs. But the real question for a business owner like you isn’t just "does it work?" but "will it work reliably for a million cycles?" The success of a slider lies in the details—the components that drive its movement, the forces that lock it in place, and the design choices that prevent it from failing under pressure. Let’s dive deeper into these critical elements to see how a truly robust slider system is built.

What Are the Key Components of a Slider System?

You have the idea that you need a slider in your design, and a drawing of a mold can be daunting to look at. All these various parts that you see and you wonder what each of them does and why they are there. The failure to design or even neglecting to design any of these parts may result in severe consequences such as defects in parts, premature degradation or even disastrous mold failure. It is not a technical issue only, but a business issue that can put your production line to a stop.

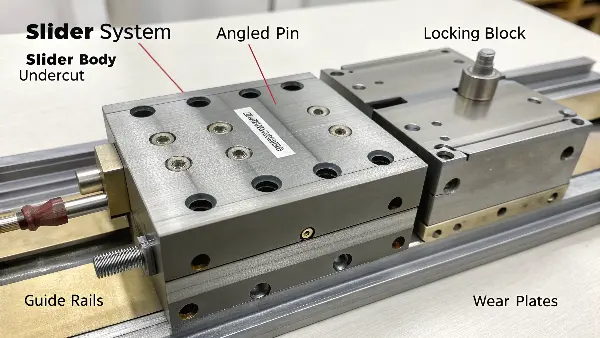

Any competent slider system is constructed out of four fundamental components in harmony with each other. The first is the slider body that is a portion that makes the actual undercut. Second is the angled pin, which gives motion to the slider. Third is the locking block, which is also called the heel that keeps the slider firmly attached to the injection pressure that is enormous. Lastly, slider guide rails, wear plates provide the slider to travel with ease and precision through thousands of cycles. Knowledge of the role of each component is to a key to a reliable mold design.

Getting these components right is the foundation of a high-performance mold. I’ve seen molds fail prematurely simply because one of these areas was overlooked. Let’s break down each part to understand its specific job and why it’s so critical to your final part quality and the mold’s lifespan.

The Slider Body: The Heart of the Feature

The slider body is the part of the mechanism that directly contacts the molten plastic to form your desired undercut, whether it’s a clip, a vent, or a side hole. Its shape is a negative of the feature you want to create. Because it’s a core-side component that moves, its material and construction are critical. We typically use durable, hardened tool steels like H13 or S7 to withstand the repeated thermal and mechanical stress. The surface finish on the slider body is also vital; it must be polished smoothly in the direction of release to prevent the plastic from sticking, which could otherwise damage the part during ejection.

The Angled Pin: The Engine of Movement

The pin is the angled pin, which is at times referred to as a cam pin though it happens to be the engine that powers the whole system. It is a straight, hardened steel rod fastened on the stationary half of the mold in a given angle. When the mold is opened, the pin is left behind in the slider deflecting it and away from the plastic part.

The inclination of this pin is a design decision. A shallow angle (e.g. 15 degrees) offers a high mechanical force to shift a heavy or crowded slider, however with a lengthy stroke in the opening of the mold. A steeper angle (e.g. 25 degrees) is fast with less force, but the opening of the mold is less. Most common is 15 to 25 degrees and we select the angle depending on the requirements of the part, such as undercut depth and weight of the slider.

The Locking Block (Heel): The Unsung Hero

The locking block, or heel, is arguably the most important safety and quality feature in a slider design. When the mold is closed and plastic is injected, the pressure can be immense—often thousands of pounds per square inch (PSI). This pressure pushes directly on the slider body, trying to force it backward. The locking block is a solid steel block that sits behind the slider, absorbing this force and preventing any movement. Without a robust locking block, the slider would be pushed back, creating a gap and causing ugly, unacceptable plastic "flash" on the part. We design these with a slight angle (the lock angle, typically 2-5 degrees) to ensure a tight, secure fit before injection begins.

Guide Rails and Wear Plates: Ensuring Longevity

There is a slider that slides back and forth each and every cycle. There was a lot of moving over a million parts run of production. Galling, wear, and friction will occur due to the steel on steel interaction, to avoid this, we employ guide rails and wear plates. Guide rails keep the slider in a thoroughly straight path so that it is in contact with the part. In between the moving slider and the fixed base of the mold, wear plates are used, which may be of a special bronze alloy or of self-lubricating material (such as graphite-plugged Oiles plates). They do so by giving a low friction surface that is easily replaced should the mold base that is costly be damaged in the long run.

| Component | Primary Function | Key Design Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Slider Body | Forms the undercut feature on the part. | Material hardness, surface finish, and cooling. |

| Angled Pin | Drives the slider’s movement. | Angle (15°-25°), length, and material hardness. |

| Locking Block | Secures the slider against injection pressure. | Surface area, locking angle, and material strength. |

| Wear Plates | Reduce friction and prevent wear. | Material (e.g., Oiles), lubrication, and fit. |

How does a slider work in injection molding?

There are no circuits or hydraulic cylinders in the slider, so how does it get the power? The angled guide post provides the power to the slider system through its motion. In the process of the mold opening and closing, the angled guide post creates friction with the inner wall of the slider. This is the friction force that causes the whole slider system to move in a direction that is perpendicular to the demolding direction.

8 Ways to Achieve Undercut Success in Molded Parts

Undercuts are needed in plastic injection molding to form complex geometries such as holes, threads and snap fits–but increase the difficulty of molding and ejection. Uncontrolled undercuts may hike the prices of tooling as well as slow down production. Designers have to strike a balance between creativity and manufacturability to attain smooth, cost-effective molding. These are eight sure methods of guaranteeing that undercut failure occurs.

1. Learn the Kinds of Undercuts.

The initial step involves the identification of the two major forms of undercuts which include external and internal. External undercuts are on the surface, like holes or side grooves, whereas the internal are inside the cavities, like threads or grooves. The distinction assists the engineers to select the appropriate tooling method, either slides, lifters, or collapsible cores, which result in a more effortless part release and fewer manufacturing hitches.

2. Reduce Undercuts at all Costs.

Undercuts provide flexibility in the design, however, they must be reduced to the lowest necessary extent to make moulding easier. Such a minor geometry rearrangement as altering a snap-fit, or cutting the part in half, may sometimes make an undercut unnecessary at all. Minimizing complexity does not only reduce the cost of the tooling, but also reduces the cycle time and enhances the overall mold durability.

3. External Undercuts Use Side Actions

Side actions or slides are a good solution when the use of external undercuts is inevitable. In the opening of the molds, the slides slide sideways to release such characteristics of the object as holes or slots. To operate consistently they have to be in a perfect fit, lubricated correctly, and slide angles are usually in the range of 10 ° to 20 °. An efficient slide mechanism would guarantee the dependability of the part release in a manner that would not destroy the surface.

4. Install Lifters on Internal or Deep Undercuts.

Lifters should be used in the case of undercuts, internal or inaccessible. When they are thrown off they do so in a diagonally inclined manner, and liberate internal features such as angled recesses. Lifters must be of wear-resistant material, and they must be timed with the ejector system. Adding correct draft angles can assist in good removal and avoid deformation of parts and stress marks when releasing parts.

5. Collapsible Cores may be considered with Circular or Threaded Undercuts.

Collapsible cores are compact and efficient when it comes to molding internal threads, circular recesses or grooves. As they are injected, they swell to create the undercut, which shrinks as they are expelled with easy release. Collapsible cores do not require elaborate unscrewing, and that is why they are suitable to high-volume production which requires speed and accuracy.

6. Apply Controlled Deformation or Flexible Materials.

In case the material of the part is flexible (PP, TPE, TPU, etc.), small undercuts can be frequently released without special tooling. The component merely collapses a bit in the ejection process and then gets back to shape. It is best applied in shallow undercuts (less than 1 mm) and components that are sufficiently elastic to allow full recovery, which helps to simplify and lower the cost of tooling.

7. Maximize Draft angels and Surface Finishes.

Undercut molding is very sensitive to proper draft angle and finish of the surface. Sticking may occur or parts may be damaged even with slides or lifters because of a lack of sufficient draft. A review of 3-5deg and a smooth or slightly rough finish assist parts in escaping with ease. These are design enhancements which minimize friction, scuffing, and the duration of the life of moulds.

8. Cooperate with Design and Tooling Workforce.

Lastly, early coordination between the product designers and the tooling engineers is required in undercut success. When the risks in the design phase are discussed, it is easier to make adjustments before production. CAD and mold flow simulation can also be used to find problems at an early stage to avoid expensive. An amicable strategy makes the mold efficient, dependable, and production-oriented.

Undercuts add flexibility and strength to the molded components though planning and collaboration are necessary. The manufacturers can attain quality production with minimal complications through the knowledge of undercut type, eliminating complexity in designs, appropriate tooling solutions and solid communication between teams. The secret of innovation that integrates both efficient manufacturing and innovation lies in smart undercut design.

How Do You Calculate the Slider’s Travel Distance?

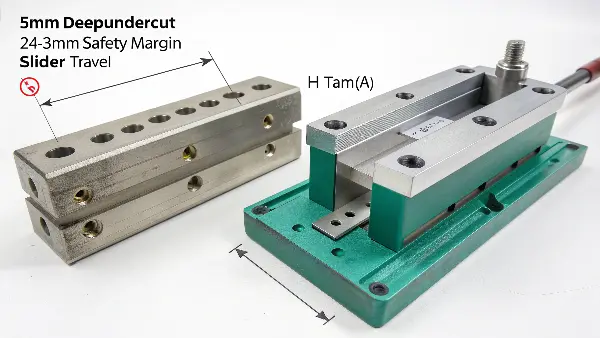

You have created one with a great snap-fit part that has a 5mm deep undercut. You know it is a slider but how do you figure out in what way the slider must go and more importantly what extent of opening must the whole mold have? Guessing is a matter of disaster. Should the slider not move far enough, it will collide with the pins of ejector or destroy the part as it moves through them. When it encodes too far, then it will be wasting precious seconds on each cycle which translates to enormous expenses in the long run of production.

The calculation of the travel of the slider involves taking the depth of the undercut and adding a small safety amount (typically 2-3mm) so that it clears fully. this provides you with the necessary Slider Travel (S). Then you simply apply a trigonometry equation on the basis of the angle of the angled pin ( 0): H = S / tan (0). This computation makes sure that this slider does not withdraw too far before part ejection starts to make sure that release is clean each and every time without a wasted motion.

This might seem like complex engineering, but it’s a straightforward process that every good mold designer follows meticulously. It’s the difference between a mold that works on paper and a mold that works flawlessly in the press. Let me walk you through a practical example so you can see exactly how we ensure everything moves in perfect sync.

Step 1: Determine the Undercut Depth (U)

First, we look at the part drawing. Let’s stick with our example of a snap-fit clip that requires a 5mm deep undercut. This is the absolute minimum distance the slider face must move away from the part’s centerline before the part can be ejected vertically.

- Undercut Depth (U) = 5mm

Step 2: Add a Safety Margin for Slider Travel (S)

In manufacturing, we never design to the absolute minimum. What if the machine’s opening stroke varies slightly? To be safe, we must ensure the slider is completely out of the way. A standard industry practice is to add a safety margin of 2mm to 3mm. This extra distance provides a buffer, guaranteeing clearance. For our example, let’s add 3mm.

- Required Slider Travel (S) = Undercut Depth (U) + Safety Margin

- S = 5mm + 3mm = 8mm

So, our slider must be designed to travel a total of 8mm.

Step 3: Choose an Angled Pin Angle (α)

Now we must select the angle for the pin that will drive this movement. As I mentioned, this is a balancing act. A 20-degree angle is a very common choice because it offers a good mix of force and efficient travel. Let’s use that for our calculation.

- Angled Pin Angle (α) = 20°

Step 4: Calculate the Required Mold Opening Stroke (H)

Here’s where we use the simple formula. The mold opening stroke (H) is the vertical distance the press opens. The slider’s travel (S) is the horizontal distance it moves. The relationship is defined by the tangent of the pin’s angle.

- Formula: H = S / tan(α)

- H = 8mm / tan(20°)

- The tangent of 20 degrees is approximately 0.364.

- H = 8mm / 0.364 ≈ 21.98mm

We would round this up to 22mm. This means that for our slider to move back 8mm, the molding machine must be programmed to open at least 22mm before the ejector pins activate. This simple calculation prevents collisions and ensures a smooth, efficient process.

| Pin Angle (α) | Tan(α) | Required Mold Opening (H) for 8mm Slider Travel | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15° | 0.268 | ~29.85 mm | More force, but slower; needs more opening. |

| 20° | 0.364 | ~21.98 mm | Good balance of force and speed. |

| 25° | 0.466 | ~17.17 mm | Faster, needs less opening, but provides less force. |

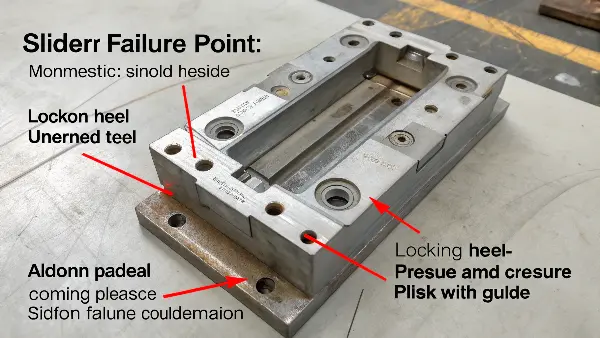

What Are the Most Common Failure Points in Slider Designs?

Your new toddler is running, and the initial parts look superb. However, after several thousand cycles, an operator observes that there is a thin strip of plastic flash at the undercut. Production stops. Mold needs to be removed out of the machine in order to maintain it. You’re losing time and money. Such situation is annoyingly familiar and it nearly always boils down to a handful of failure points in the design of the slider that were missed. These problems do not necessarily manifest themselves immediately but they appear in the course of time as the stress on the mold takes place.

Three main problems result in the most common feebles of the slider. The first is that of poor locking heel, resulting in injection pressure pushing back the slider resulting in flash. Second is the premature wear of the angled pin or guide surfaces of friction and galling which causes sloppy movement and misalignment. Third is lack of cooling of the slider body and this results in part defects and also high cycle time. The most important thing to a mold that will ultimately run smoothly throughout its intended duration is to plan against these three weaknesses.

As I have been able to experience over the many years of my experience in building and outside trouble shooting molds, it costs a lot more to fix than it does to prevent these issues. A good mold is not a novelty; the secret of a good mold is planning and creating a mold that would be durable at the start of the molding process. We may see how to counter such plays of the antagonistic to production efficiency.

Failure #1: The Dreaded Flash from Lock Failure

This is the number one killer of part quality in slider molds. Flash occurs when the locking block (heel) isn’t robust enough to withstand the incredible pressure of the injected molten plastic. Even a tiny movement of the slider—as small as 0.02mm—is enough to create a gap that plastic will escape into.

- Cause: The force of the plastic injection is greater than the holding force of the locking block. This is usually due to the locking block having too small of a surface area or being made from a material that’s too soft.

- The Proactive Solution: When I design a mold, I calculate the projected surface area of the slider that will be exposed to plastic pressure. Then, I calculate the force based on the maximum injection pressure of the material. The locking block must be designed to be strong enough to resist this force with a significant safety factor. Using a large, hardened steel block is not an option; it’s a necessity.

Failure #2: Galling, Seizing, and Sloppy Movement

Galling is what happens when two pieces of steel rub against each other under pressure without proper lubrication. The surfaces begin to tear and weld themselves together, creating friction and causing jerky, unreliable movement.

- Cause: This typically happens between the angled pin and the slider, or between the slider body and its guide rails. It’s a direct result of poor material selection or a lack of planned lubrication.

- The Proactive Solution: This is where smart material choices are critical. We never run hardened steel directly against an identical hardened steel. We use dissimilar materials or, more commonly, install specialized wear plates. As I mentioned before, components like Oiles wear plates, which are bronze-infused with graphite plugs, provide continuous self-lubrication. We also design literal grooves (lubrication channels) into the mold base so that grease can be easily applied during maintenance to all moving parts.

Failure #3: Overheating and Warpage

The slider is a solid piece of steel that is constantly being heated by molten plastic. If that heat isn’t removed efficiently, the slider will run much hotter than the rest of the mold.

- Cause: A lack of dedicated cooling channels within the slider body itself. The heat has nowhere to go.

- The Proactive Solution: This leads to two problems: first, the part feature formed by the slider takes much longer to cool, extending the overall cycle time. Second, uneven cooling can cause the part to warp as it solidifies. The solution is to design cooling circuits directly into the slider whenever possible. For larger sliders, we drill water lines through them. For smaller or more complex sliders, we can use a modern technique called conformal cooling, where we 3D print a metal insert with cooling channels that follow the exact contour of the slider, providing incredibly efficient heat removal. This investment up front pays for itself by reducing cycle time and improving part quality.

Conclusion

Slider is not merely a trick; it is one of the essential elements of productions of high quality, intricate plastic parts with undercuts. Their achievements will depend on sufficient knowledge of their essentials, determining the accurate calculation of their movement, and proactive design style that foresees and eliminates most failures such as wear and poor locking. A good slider is a guarantee of quality, efficiency and profitability and your ambitious piece of work is brought to life in the solid reality of mass production. It is the way, how we Master Mold.