Do you have problems with injection molding defects such as warping, burn marks, or weak parts? The problem can be rooted in the wrong temperature settings from day one, which means wasted material, projects taking much longer, and unhappy clients. The struggle is on to find that sweet thermal spot that differs from plastic to plastic. What if you could dial in the right temperatures every single time, ensuring flawless production runs and becoming an expert others can rely on?

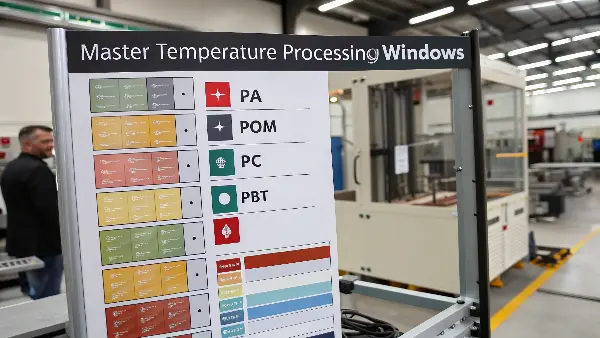

**Mastering the temperature processing window involves three key areas: barrel temperature, melt temperature, and mold temperature. In dealing with common engineering plastics, you have to pre-dry the material thoroughly. Then, set the barrel temperature in zones-usually in an increasing order from the feed throat to the nozzle. For example, PC requires high temperatures (280-320°C barrel, 80-120°C mold), while POM has a much narrower window (190-210°C barrel, 80-100°C mold) and degrades quickly if overheated. Each plastic has a unique profile that you need to respect if you want to be successful.

Getting the temperature right feels like a secret art, but it’s really a science. I remember early in my career, we had a huge order for automotive components. We followed the general guidelines but kept getting inconsistent results. It wasn’t until we started meticulously documenting and mapping the specific windows for each material, almost creating our own internal encyclopedia, that we achieved the consistency we needed. That experience taught me that general knowledge gets you started, but deep, specific knowledge makes you a master. In this article, I want to share that deeper knowledge with you, so you can skip the trial and error and get straight to predictable, high-quality results.

Why does mold temperature matter just as much as barrel temperature?

Are you focusing all your attention on nozzle-and-barrel heat while ignoring your mold temperature? This common oversight opens the door to a host of problems, from poor surface finish to internal stress that causes parts to fail later. You think you’ve solved the problem by adjusting the melt temperature, but the parts still come out warped or brittle. It’s frustrating to chase a problem that seems to have no clear source, all while production schedules slip.

Mold temperature is crucial to control since it regulates the rate at which the plastic cools. This, in turn, directly affects the final properties of the part, such as crystallinity, shrinkage, internal stress, and surface appearance. If the mold is too cold, the plastic "freezes" before it completes filling the cavity, resulting in short shots. If the mold temperature is too hot, the cycle times will increase with possible defects like sink marks or warpage. Matching the mold temperature to material-specific needs ensures predictable, high-quality results.

Let’s dive deeper into why this is so fundamental. The journey of the plastic doesn’t end when it leaves the nozzle; in many ways, it’s just beginning. The state change from molten liquid to a solid, stable part happens inside the mold, and temperature is the conductor of that entire process. You can have the most perfectly prepared and heated melt, but if it hits a mold surface that’s at the wrong temperature, all that preparation is wasted. I like to think of barrel temperature as preparing the material for its mission, while mold temperature is the environment where the mission is actually accomplished. Ignoring it is like sending a soldier into the arctic with summer gear – the outcome is not going to be good.

Controlling the Final Part Properties

The temperature of the mold cavity surface is a primary driver of the final part’s performance. It’s not just about getting the plastic to solidify; it’s about how it solidifies.

- Crystallinity: For semi-crystalline plastics like PA, POM, and PBT, mold temperature is everything. A warmer mold allows the polymer chains more time to organize into crystalline structures before freezing. This leads to parts with higher stiffness, strength, and chemical resistance. A cold mold freezes the material in a more amorphous state, resulting in a weaker part.

- Internal Stress: A large temperature difference between the molten plastic and the mold surface creates significant internal stress. A cold mold shocks the material, causing the outer layers to solidify instantly while the core is still molten. As the core cools and shrinks, it pulls on the rigid outer skin, locking in stress. This can lead to warpage or premature failure in the field. A properly heated mold reduces this thermal shock, allowing the part to cool more uniformly and minimizing stress.

Impact on Aesthetics and Dimensions

Beyond mechanical properties, mold temperature directly affects how the part looks and measures up.

| Aspect | Impact of Low Mold Temp | Impact of High Mold Temp | Ideal Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Finish | Dull spots, flow lines, poor replication of texture. | High gloss, excellent texture replication. | A smooth, uniform surface that matches the design intent. |

| Shrinkage | Lower, less predictable shrinkage. May seem good initially. | Higher, but more uniform and predictable shrinkage. | Consistent part dimensions that are within tolerance. |

| Warpage | Often higher due to differential cooling and stress. | Lower, as the part cools more evenly. | A flat, stable part that holds its intended shape. |

| Cycle Time | Faster cooling, but may require longer hold times. | Slower cooling, directly increasing cycle time. | An optimized cycle that balances speed with part quality. |

Ultimately, a slightly longer cycle time caused by a higher, correct mold temperature is almost always cheaper than dealing with a batch of rejected parts caused by rushing the cooling process with a cold mold.

What is the PC melting point?

Polycarbonate (PC) lacks a actual melting point being an amorphous thermoplastic. PC does not transform into a liquid at a given temperature as crystalline plastics do and instead, it gets softened slowly with an increase in temperature. PC has its most important reference point in its glass transition temperature (Tg), which is approximately 147 deg C. The material will change to a softer, rubber-like material at this temperature, with the material being in the hard and glassy state.

In practical manufacturing, PC is molded at significantly higher temperatures in order to obtain the correct flow of the melt. Common processing temperatures fall within the 260 deg C to 300 deg C. This is what enables injection PC into molds at a high temperature, despite the fact that the material in fact never actually melts in the crystalline sense.

The Vicat softening point of polycarbonate is also within the range of 150-160degC, at which it starts to creep under the weight. The decomposition process typically begins above 320 deg C hence it is important to remain within the recommended processing range to prevent burning or yellowing. Generally, PC does not melt as most plastics; however, the knowledge of its softening temperature and processing temperature guarantees consistently high quality and no fluctuating results in production.

Why is the PC melting point important in manufacturing?

Melting point of the PC is a critical parameter to define the behavior of the material, during the fabrication process. Not enough heat, and the mold will not fill, and the plastic will not fill to form a complete part, which will be weak. Excessive heat and the chains of polymer can start degrading, which causes discoloration, distortion, and deteriorated performance.

The knowledge of this melting range is crucial in injection modeling, extrusion, and 3D printing. In injection molding, temperatures in barrels are usually kept between 270degC to 320degC, and the mold is kept at temperatures of between 80 °C and 120 °C so that it can cool well and be demolded easily.

In 3D printing (FDM), PC filament needs higher temperatures in comparison to common plastics such as PLA. The extruder will need to reach 270degC to 310degC and the print bed frequently requires heating to 100degC or higher in order to prevent warping. This renders PC a difficult yet very beneficial additive manufacturing material.

What are the specific temperature settings for Polyamide (PA) plastics?

Have you ever molded PA (Nylon) perfectly one day, only to have a brittle, useless batch the next using the same machine settings? This inconsistency is a classic symptom of ignoring one of the most important properties of PA: its love for moisture. You scratch your head, feeling that the material or the machine is letting you down, when the real culprit is hidden moisture and poorly optimized temperature profile, costing you a great deal of time and material.

Drying of Polyamide (PA) to below 0.2% moisture requires drying at 80-90°C for 4-6 hours. The barrel temperature is usually started at approximately 230°C in the rear and cranked up to 260-290°C at the nozzle, depending on the grade (PA6 vs. PA66). Mold temperature is important for the level of crystallinity desired, and a range between 60° and 100°C would be generally recommended. A hotter mold provides a stronger, more stable part, although it may increase cycle time somewhat.

I learned the PA lesson the hard way on a project for a client who needed high-strength gears. For weeks, we blamed a bad batch of PA66 when parts kept failing our impact tests. They were just too brittle. It turned out our material handler was cutting corners on drying times. Once we enforced a strict drying protocol and raised our mold temperature by 15°C to improve crystallinity, the parts started coming out perfectly. That’s a reminder that with PA, you are not just melting plastic but managing its relationship with water and heat from start to finish.

The Critical First Step: Drying

Before you even think about melting Polyamide, you must think about drying it. PA is hygroscopic, meaning it absorbs moisture from the surrounding air. If you try to process undried or improperly dried PA, the water inside the pellets turns to steam at processing temperatures. This steam attacks the polymer chains, breaking them down in a process called hydrolysis. The result is a part with drastically reduced mechanical properties, making it brittle and weak.

- Drying is non-negotiable: Never skip this step. Even freshly opened bags can have surface moisture.

- Proper equipment: A desiccant dryer is essential. It provides the low-dew-point air needed for effective drying. A simple hot air oven will only heat the pellets; it won’t remove the moisture effectively.

Differentiating PA6 and PA66

While often grouped together, PA6 and PA66 have slightly different processing requirements due to their different molecular structures. PA66 generally has a higher melting point and requires slightly higher processing temperatures.

Here is a general guide. Always start with the material supplier’s datasheet, but these values provide a solid starting point for optimization.

| Parameter | Polyamide 6 (PA6) | Polyamide 66 (PA66) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drying Temperature | 80°C (175°F) | 85°C (185°F) | Dry for 4-6 hours to <0.2% moisture. |

| Melt Temperature | 230 – 280°C (446 – 536°F) | 260 – 290°C (500 – 554°F) | PA66 is more sensitive to thermal degradation. |

| Mold Temperature | 60 – 90°C (140 – 194°F) | 70 – 100°C (158 – 212°F) | Higher temps for glass-filled grades to improve surface. |

| Nozzle Temperature | 240 – 280°C (464 – 536°F) | 270 – 290°C (518 – 554°F) | Should be slightly lower than barrel front zone to prevent drool. |

| Barrel Zone 1 (Rear) | 220 – 240°C (428 – 464°F) | 240 – 260°C (464 – 500°F) | Lower temp to prevent premature melting. |

| Barrel Zone 2 (Middle) | 230 – 260°C (446 – 500°F) | 260 – 280°C (500 – 536°F) | Gradually increase temperature. |

| Barrel Zone 3 (Front) | 240 – 280°C (464 – 536°F) | 270 – 290°C (518 – 554°F) | Hottest zone to ensure full melt. |

Remember, for glass-filled (GF) variants, you often need to run at the higher end of these temperature ranges. The glass fibers increase viscosity, so higher temperatures are needed to ensure the mold fills properly and to achieve a good bond between the polymer and the fibers, which is critical for strength.

How do you set temperatures for Polyoxymethylene (POM) and Polycarbonate (PC)?

Are you treating all plastics the same and finding that POM parts are degrading while PC parts won’t even fill the mold correctly? Such an approach is a common but very costly mistake. POM is extremely sensitive to overheating, while PC demands very high heat to flow. Mixing up their requirements leads to burned material, clogged nozzles, short shots, and a lot of wasted machine time, putting your entire production schedule at risk.

POM: Using a narrow and well-defined temperature window, set the barrel temperatures from 180°C (rear) to 210°C (nozzle), with a melt temp around 205°C. Very importantly, POM cannot be left sitting at temperature for very long since it degrades. For PC, you’ll need very high heat; pre-dry it thoroughly and then set barrel temperatures from 260°C (rear) up to 310°C (nozzle); use a hot mold (80-120°C) to ensure the highly viscous material can fill the cavity properly and get a good surface finish.

These two materials taught me about respecting the extremes of the processing spectrum. I recall a job using POM for several low-friction sliding parts. An operator took an extra-long lunch and left the machine sitting with a full barrel of molten material. When he returned, the material had degraded and was emitting formaldehyde gas-a serious safety concern. On the other end of the scale, we fought for days with a large PC housing that had flow lines everywhere. The solution was counterintuitive: we had to crank up both the barrel and mold temperatures far higher than we were comfortable with to get the beautiful, glossy finish the client demanded.

Processing Polyoxymethylene (POM / Acetal)

POM is a fantastic material known for its lubricity, stiffness, and dimensional stability. However, it is thermally sensitive and has a very narrow processing window. Exceeding its processing temperature doesn’t just damage the part; it causes the material to degrade and release pungent, hazardous formaldehyde gas.

- Key Challenge: Thermal Stability. Never let POM sit idle in a heated barrel for extended periods. If there’s a stoppage, purge the barrel immediately.

- Temperature Control: Precision is vital. The difference between a good part and a degraded mess can be as little as 10-15°C.

- Mold Temperature: A warm mold (80-100°C) is essential for controlling its high crystallinity and minimizing shrinkage and warpage.

Typical POM Processing Temperatures:

| Parameter | POM (Acetal) | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Drying | 80 – 90°C (175 – 195°F) for 3-4 hours | Although low moisture absorption, drying is recommended for consistency. |

| Melt Temperature | 190 – 210°C (374 – 410°F) | Do NOT exceed 215°C. The window is very narrow. |

| Mold Temperature | 80 – 100°C (175 – 212°F) | Critical for controlling crystallinity and reducing post-mold shrinkage. |

| Nozzle Temp | 195 – 210°C (383 – 410°F) | Set slightly higher than the front zone to ensure smooth flow. |

| Barrel Profile | 180°C (Rear) -> 205°C (Front) | A gentle, progressive heating profile works best. |

Processing Polycarbonate (PC)

Polycarbonate is a tough, transparent, and impact-resistant amorphous thermoplastic. Its main processing challenge is its extremely high viscosity when molten. It flows like thick honey, not water. This means it requires high temperatures and pressures to force it into the mold cavity.

- Key Challenge: High Viscosity. PC needs a lot of heat to flow properly.

- Drying: Like PA, PC is hygroscopic. It MUST be dried thoroughly before processing (typically 120°C for 4 hours) to prevent splay marks and brittleness.

- Mold Temperature: A very hot mold (80-120°C) is not optional; it’s required. It keeps the plastic molten longer, allowing it to pack out the cavity, replicate fine details, and reduce internal stresses.

Typical PC Processing Temperatures:

| Parameter | Polycarbonate (PC) | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Drying | 120°C (250°F) for 3-4 hours | Absolutely essential. Moisture content must be below 0.02%. |

| Melt Temperature | 280 – 320°C (536 – 608°F) | This high temperature is needed to reduce viscosity for proper flow. |

| Mold Temperature | 80 – 120°C (175 – 250°F) | Prevents premature freezing and weld lines. Higher temp = better finish. |

| Nozzle Temp | 285 – 310°C (545 – 590°F) | Must be kept high to prevent freeze-off in the nozzle tip. |

| Barrel Profile | 260°C (Rear) -> 310°C (Front) | A significant temperature ramp is needed to handle the high viscosity. |

Treating POM with caution and PC with assertive heat are two sides of the same coin: respecting the unique chemistry of the material you are working with.

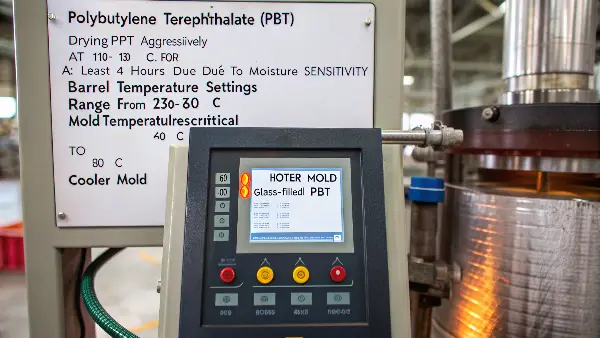

What makes Polybutylene Terephthalate (PBT) tricky, and what are its ideal temperatures?

Are your PBT parts warping unpredictably or failing quality checks for dimensional stability? You might be fighting against PBT’s two defining characteristics: its extreme sensitivity to moisture during processing and its very rapid crystallization rate. If you don’t manage these factors with precise temperature control, you’ll produce parts with poor surface finishes and dimensions that are all over the place, leading to high scrap rates and project delays.

PBT is highly susceptible to hydrolysis, and, therefore, it must be dried aggressively at 110-130°C for no less than 4 hours to process it successfully. The barrel temperature profile is 230-260°C, and a melt temperature of 240-275°C should be used. The mold temperature is critical and varies between 60°C and 90°C. A cooler mold, ~60°C, will allow improved surface gloss, while a hotter mold, ~90°C, can be used with glass-filled grades to minimize warpage and ensure dimensional stability.

PBT is a workhorse in the electronics industry, especially for connectors and housings, and I’ve worked with it extensively. One of the trickiest things is its rapid setup time. It crystallizes and solidifies very quickly. This is great for fast cycle times, but it means your processing window is small. If your melt or mold temperature is too low, the material can freeze before the mold is fully packed out, causing sinks and voids. It’s a material that demands your full attention to detail from the dryer to the mold.

The Double Challenge: Hydrolysis and Crystallization

PBT presents a unique combination of challenges that you must manage simultaneously.

- Susceptibility to Hydrolysis: Like PA and PC, PBT is hygroscopic. However, it is particularly vulnerable to hydrolysis at melt temperatures. Any residual moisture will chemically sever the long polymer chains. This isn’t something you can see, but it drastically weakens the material, making it brittle. The drying step for PBT is arguably the most critical part of the entire process. Do not compromise on it.

- Rapid Crystallization: PBT is a semi-crystalline material, but it crystallizes much faster than something like PA. This rapid solidification can be a benefit (fast cycles) or a curse. If the cooling is not uniform, it will lead to significant differential shrinkage, which is the primary cause of warpage in PBT parts.

Finding the PBT Sweet Spot

Your temperature strategy for PBT must balance the need for good flow against the need to control its rapid cooling. Using a temperature that’s too high can cause degradation, while one that’s too low will cause flow problems and poor part quality.

Here’s a structured look at the ideal temperature settings:

| Parameter | PBT (Unfilled) | PBT (Glass-Filled) | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drying | 120°C (250°F) for 4 hours | 130°C (265°F) for 4 hours | Must be bone dry (<0.02% moisture). Hydrolysis is a major risk. |

| Melt Temperature | 240 – 260°C (464 – 500°F) | 250 – 275°C (482 – 527°F) | Glass-filled grades need more heat to flow. |

| Mold Temperature | 60 – 80°C (140 – 176°F) | 70 – 90°C (158 – 194°F) | This is the key to controlling warpage. Hotter is often better. |

| Nozzle Temp | 235 – 250°C (455 – 482°F) | 245 – 265°C (473 – 509°F) | Keep hot, but watch for drooling. |

| Barrel Profile | 230°C (Rear) -> 250°C (Front) | 240°C (Rear) -> 265°C (Front) | A smooth ramp works well. |

For PBT, the mold temperature is your primary weapon against warpage, especially for glass-filled grades where fibers orient and cause uneven shrinkage. While a colder mold might give you a slightly faster cycle, the cost of dealing with warped, out-of-spec parts will quickly erase those gains. When in doubt, start with a hotter mold (around 80-90°C). This allows the part to cool more slowly and uniformly, relieving internal stresses and giving you a much more dimensionally stable final product.

Conclusion

The temperature settings for engineering plastics are not black magic, but rather a science-one of respect for the particular properties of each material. From precise drying to the balancing act between the temperature of the barrel and mold, it all requires accuracy. By understanding what PA, POM, PC, and PBT specifically require, you will move from fighting defects to producing high-quality parts constantly. Understanding these requirements will transform you from a machine operator to a true molding expert and save time, material, and money on each project.