Have you ever inspected a freshly molded plastic part, only to find small, unsightly marks on its surface? These blemishes, often caused by ejector pins, can ruin an otherwise perfect product and lead to costly rejects. It’s a common frustration in manufacturing. The solution often lies hidden in your initial material selection, a choice that dictates how cleanly a part will release from its mold.

The choice of plastic material directly influences both the ejection force needed and the likelihood of ejector pin marks. Materials with high shrinkage rates, poor flow, or higher elasticity tend to grip the mold core tightly. This requires a greater ejection force, which can cause the pins to leave marks, dents, or even whitening on the plastic surface. Conversely, materials with good flow, low shrinkage, and inherent lubricity release more easily, reducing both the required force and the risk of cosmetic defects.

Understanding the link between your material and potential ejection issues is crucial for any project’s success. It’s not just about avoiding ugly marks; it’s about ensuring a smooth, efficient, and cost-effective production run. The deeper you dive into how specific material properties behave inside the mold, the more control you’ll have over the final quality of your parts. Let’s explore this connection further to help you make better material choices from the start.

What an Ejector Pin Mark on a Plastic Product Actually Is?

You’ve designed a great product and the mold is ready, but the first samples have small circular impressions on them. You might wonder if the mold is flawed or if the process is wrong. These marks often point directly to the ejection stage. Getting to the bottom of this issue starts with understanding exactly what these marks are and why they appear on your carefully crafted parts.

An ejector pin mark is a surface imperfection on a molded plastic part created by the pressure of an ejector pin during its removal from the mold. These marks can appear as shiny or dull spots, slight indentations, raised bumps, or white stress marks. They occur when the ejection force required to push the part off the mold core exceeds what the plastic can withstand in its semi-solid state. This indicates an imbalance between material properties, part design, and the ejection system.

To really grasp this, we need to look at the ejection process itself. After the plastic is injected and cools, the mold opens. At this point, the part is still clinging to one half of the mold, usually the core side, due to natural shrinkage. The ejector system, a series of steel pins, then pushes forward to separate the part from the mold. This is a critical moment. If everything is balanced, the part pops off cleanly. But if the part sticks too strongly, the pins exert immense localized pressure.

The Mechanics of Mark Formation

The plastic is still warm and not fully hardened when ejection occurs. Think of it like pushing your finger into a cake that has just come out of the oven. If you push too hard, you leave a permanent mark. It’s the same principle. The force from the pin concentrates on a small area. This can compress the plastic, creating a dent, or stretch it, causing whitening.

Common Types of Ejector Marks

Not all marks are the same. Recognizing them can help diagnose the root cause. I’ve seen countless variations over the years, but they usually fall into a few categories.

| Mark Type | Description | Common Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Indentation | A slight depression or dimple. | Excessive ejection force on a still-soft part. |

| Whitening | A white, stressed area around the pin location. | High force on brittle plastics like Polystyrene. |

| Protrusion | A raised bump on the part surface. | Pin is too long or flashing occurs around the pin. |

| Shiny/Dull Spot | A change in surface texture. | Pin polishing doesn’t match the mold texture. |

Understanding these details is the first step. Next, we’ll look at how your material choice makes the part either stick like glue or release with ease.

How Do Different Plastic Properties Affect Ejection Force?

Your part design is perfect and your mold is flawless, but parts are still getting stuck or coming out with stress marks. This frustrating problem can bring production to a halt. You might start blaming the machine settings or the mold design. But often, the real culprit is the plastic itself. Its inherent properties are creating the friction and adhesion that the ejection system has to fight against.

A plastic’s properties, primarily its shrinkage rate, coefficient of friction, and flexural modulus, are key factors determining ejection force. High-shrinkage materials grip the mold core tightly, increasing the force needed for release. Materials with a high coefficient of friction create more resistance. Flexible materials can warp or bend under pin pressure instead of releasing cleanly. Choosing a material that balances these properties is essential for minimizing ejection force and preventing part defects.

The relationship between a plastic resin and the steel mold is a physical one. When the molten plastic cools and solidifies, it shrinks. This shrinkage causes the part to clamp down tightly onto the mold core. The amount of force needed to break this grip and push the part out is the ejection force. Let’s break down the key material properties that have the biggest influence on this force.

The Critical Role of Shrinkage

Every plastic shrinks as it cools, but some shrink much more than others. Semi-crystalline materials like Polypropylene (PP) or Nylon (PA) have higher shrinkage rates compared to amorphous materials like ABS or Polycarbonate (PC). I remember a project with a deep, core-heavy part made from PP. The shrinkage was so high that the part was practically vacuum-sealed to the core. We needed a huge amount of ejection force, which stressed the part. By adding talc filler to the PP, we reduced the shrinkage and the ejection became much smoother.

Friction and Natural Lubricity

The coefficient of friction between the plastic and the mold steel is another huge factor. Some plastics are naturally "stickier" than others. For example, Thermoplastic Urethane (TPU) is notorious for its high friction, making it difficult to eject. In contrast, materials like Acetal (POM) or those with added lubricants like PTFE have a very low coefficient of friction. They release so easily that sometimes they fall out before the ejector pins even touch them.

Stiffness vs. Flexibility

The material’s stiffness, or flexural modulus, also plays a part. A very rigid material like glass-filled Polycarbonate will transfer the ejector pin force effectively and pop off the core. A very flexible material, like a soft TPE, might simply bend and deform around the pin without releasing from the mold. The pin could even puncture right through it. This is why part geometry, like draft angles, is so critical for flexible materials.

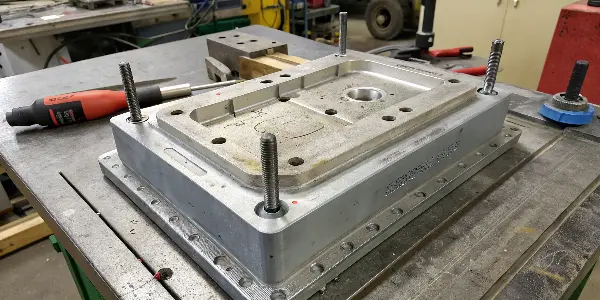

What Material Are Ejector Pins Usually Made of?

You’re focused on the plastic part, but what about the tool that pushes it out? Ejector pins are doing the hard work in every single cycle. If these pins are made from the wrong material, they can bend, break, or wear out quickly. This leads to downtime, mold damage, and inconsistent part quality. Choosing the right pin material is just as important as choosing the right plastic resin.

Ejector pins are typically made from hardened tool steels to withstand the high stress, heat, and wear of the injection molding cycle. Common materials include H-13 tool steel, which offers a great balance of toughness and heat resistance. For applications requiring higher wear resistance or lubricity, pins may be surface-treated with coatings like Titanium Nitride (TiN) or Diamond-Like Carbon (DLC), or they might be made from specialty alloys with added lubricity.

Ejector pins are unsung heroes. They operate under immense pressure and high temperatures, cycle after cycle. A standard mold might run for a million cycles, meaning the pins have to perform perfectly a million times. This requires materials with a specific set of properties to ensure they don’t fail. I’ve seen cheap, poorly made pins snap inside a mold, causing catastrophic damage that cost thousands to repair. It’s a lesson you only want to learn once.

Core Material Requirements

The choice of steel for an ejector pin isn’t random. It’s based on a few critical needs of the molding environment.

- Hardness and Strength: The pin must be hard enough to resist deforming or mushrooming under high ejection forces. It also needs the strength to not bend or buckle, especially for long, thin pins.

- Toughness: The pin has to withstand the repeated shock of pushing the part out. A material that is too hard but not tough can be brittle and snap easily.

- Heat Resistance: Ejector pins operate in a hot mold. They need to maintain their hardness and strength at elevated temperatures without softening over time.

- Wear Resistance: The pin constantly slides through guide bushings in the mold. Poor wear resistance can lead to the pin seizing up or wearing down, affecting part quality.

Common Steels and Treatments

To meet these demands, mold makers rely on a few trusted materials.

| Pin Material / Treatment | Key Feature | Best Used For |

|---|---|---|

| H-13 Tool Steel | Good all-around toughness and heat resistance. | General purpose applications. |

| Nitrided Steel | Hardened surface for high wear resistance. | High-volume production, abrasive materials. |

| Titanium Nitride (TiN) Coating | Gold-colored, very hard, low-friction surface. | Running without lubrication, sticky materials. |

| Through-Hardened Steels (e.g., A2, D2) | High hardness throughout the pin. | High-pressure applications, but can be more brittle. |

The material of the pin and the plastic part interact directly. A hard, coated pin will perform much better when ejecting a sticky, abrasive plastic than a standard, untreated pin would. This synergy is key to a robust molding process.

How Does the "Strongest" Plastic Behave During Ejection?

When customers ask me for the "strongest" plastic, they are usually looking for high tensile strength or impact resistance for their final product. But strength in the final part can sometimes mean trouble during molding. These high-performance materials often come with properties that make them grip the mold like a vise. How do you handle ejecting a part made from one of these tough plastics without damaging it?

The "strongest" plastics, like glass-filled nylons, PEEK, or Polycarbonate, often present challenges during ejection due to their high stiffness, low shrinkage, and sometimes abrasive nature. While low shrinkage reduces clamping force on the core, their rigidity means any feature that can cause binding, like insufficient draft, will require immense force to overcome. The abrasive nature of fillers like glass can also accelerate wear on the mold and ejector pins, further complicating ejection over time.

I recall a project for an automotive component using a 30% glass-filled Nylon. The part was incredibly strong, just what the client needed. However, in the first trial, we couldn’t get the parts out without causing fractures around the pin locations. The material was so rigid that it had zero "give." It wouldn’t flex or bend to release from subtle undercuts or areas with minimal draft. Instead of popping off, it was fighting the ejector pins, and the pins were winning by brute force, which damaged the part.

The Double-Edged Sword of Stiffness

High stiffness (flexural modulus) is what makes a plastic strong. This rigidity helps the part maintain its shape under load. During ejection, this means the force from the pins is transferred efficiently through the part. However, it also means the material is unforgiving.

- Positive Effect: A stiff part won’t bend or warp around the ejector pins. It is more likely to move as a single unit when pushed.

- Negative Effect: It cannot flex to release from minor imperfections or parallel surfaces in the mold. The part will either release perfectly or break. There is very little middle ground.

The Impact of Fillers

Many of the "strongest" plastics are composites, containing fillers like glass fibers, carbon fibers, or minerals. These fillers dramatically increase strength and stiffness, but they also change how the material behaves in the mold.

- Reduced Shrinkage: Fillers generally reduce the overall shrinkage rate of the base resin. This is good, as it lessens the clamping force on the mold core.

- Increased Abrasion: Glass and other mineral fillers are highly abrasive. Over thousands of cycles, they can wear down the polished surfaces of the mold and the ejector pins. This increases friction and makes ejection progressively more difficult over the life of the tool.

We solved the glass-filled Nylon issue by increasing the draft angles on all vertical walls and adding more ejector pins to distribute the force more evenly. We also used nitrided pins for better wear resistance. It shows that when you select a a strong material, you must also adapt your part and mold design to accommodate its unique ejection behavior.

Conclusion

Choosing the right plastic is about more than just the final product’s function. It directly dictates how smoothly that product can be manufactured. The material’s innate properties—its shrinkage, friction, and stiffness—are the primary drivers of ejection force and the root cause of ejector pin marks. By understanding this relationship, you can anticipate challenges and design a more robust and efficient molding process from the very beginning.