Tired of fighting molding defects like burn marks, short shots, and bubbles? These can total production runs, waste expensive materials, and delay projects. The real culprit may not be with your process or your material at all but with a critical, often-ignored detail: the venting system in your mold. Knowing how this system works is how to solve these chronic problems once and for all.

Mastering the design of the venting system means focusing on three areas: dimensions, locations, and configurations. You need to calculate the vent depth for your particular plastic material in order to allow the air to escape without allowing plastic to leak out. Next, you’ll place vents at the final fill points and anywhere air could get trapped. Finally, you select the right type of vent-parting line or pin vent-that works with the geometry of your part. Getting these elements right is fundamental to producing quality, defect-free parts consistently.

It sounds simple on the surface, but the details make all the difference. I’ve seen countless projects revived by a simple adjustment to a vent. You can troubleshoot and improve your molding operations significantly by understanding the principles behind proper venting. Let’s break down this crucial topic step-by-step. By understanding the ‘why’ behind the ‘how,’ you’ll be able to diagnose and fix venting issues like a pro.

Let’s begin with the foundational an ideas.

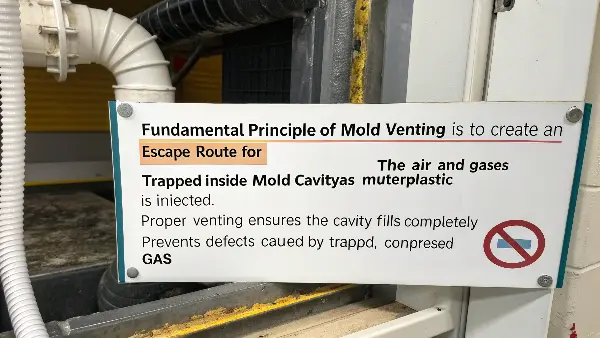

What Are the Fundamental Principles of Mold in Venting System Design?

Such a question I have always asked is why certain molds are perfectly run and certain are a continual fight? You go by all the routine and still, there are defects appearing. When you could not tell the cause of the issue, it is so frustrating. The solution is often found in the fundamental principles of the process of how air must be removed out of the mold cavity during injection. It is the beginning of consistent success to understand this.

The basic concept of the mold venting is to make a hole through which the air and gases inside the mold cavity can escape when molten plastic is being injected. This passage should have some size that would enable the gas to move away fast but at the same time small so that the plastic would not leak away. Venting properly makes sure that the cavity fills out all the way, defects due to trapped and compressed gas are avoided, and the final part is of a high quality and structural integrity.

When molten plastic rushes into a mold cavity at high speed and pressure, it displaces the air that’s already inside. If that air has nowhere to go, it gets compressed into a tiny pocket. This compression rapidly heats the air to extreme temperatures, often high enough to scorch the plastic. This is what causes those ugly brown or black "burn marks" on your parts. This phenomenon, known as the diesel effect, is a direct result of poor venting. It’s not just about the air originally in the cavity; some plastics also release volatile gases when heated, and these also need to escape.

Why Trapped Air is So Destructive

Gas that is trapped does not merely burn the plastic. It also develops back pressure which opposes the incoming flow of material. This may help the mold to fill up before it is full and hence a short shot where the part may be left incomplete. The air trapped may also pose pores or bubbles in the part forming weak points undermining the structural integrity. When I was young, I was doing a project on an electronics enclosure which could not pass drop tests. The cause? Poor venting created microscopic bubbles that could not be seen by naked eyes.

The Balancing Act of Venting in Venting System Design

The goal is to provide an easy exit for the gas without creating an escape route for the plastic. This is the core challenge. The solution lies in creating shallow channels that are deep enough for low-viscosity gas to escape but too shallow for high-viscosity molten plastic to enter. Think of it like a screen door: it lets air through easily but keeps larger things, like insects, out. In our case, the "insects" are long polymer chains. The design must be precise to maintain this balance.

| Aspect | Poorly Vented Mold | Well-Vented Mold |

|---|---|---|

| Gas Escape | Trapped, compressed, superheated | Easily escapes at low pressure |

| Cavity Filling | Incomplete fill (short shots) | Complete, uniform fill |

| Part Appearance | Burn marks, flash, sinks | Clean surface, crisp details |

| Structural Integrity | Porosity, weak weld lines | Solid, strong part |

| Cycle Time | Slower cycles to avoid defects | Optimized, faster cycle times |

Ultimately, a good venting system allows you to run your process at its optimal speed and pressure, leading to better parts, shorter cycle times, and lower costs.

What are different types of venting systems?

Ejector venting

Ejector venting involves the use of modified ejector pins with flats or grooves at the positions of the ejector pin to be removed. This technique is a combination of venting and part ejection and is therefore effective in venting deeper areas of the mold without necessarily having to add more components.

Insert venting

Insert venting involves the use of special specially designed inserts that have venting channels which can be inserted into strategic positions within the mold. This process enables accurate venting in troublesome regions and is applicable to complicated part forms.

Parting line venting

Parting line venting is used in shallow channels or grooves etched along the parting line of the mold, which are usually 0.0005 inches to 0.002 inches deep and 0.125 inches to 0.250 inches wide. This is an easy, inexpensive, and simple method to apply in the majority of mold designs.

Porous metal venting

Porous metal venting involves the use of porous metal inserts that are sintered porous metal inserts that can be installed in places where air entrapment is likely to occur. The technique enables venting in places where conventional venting is not feasible and reduces the appearance of venting marks on the part surface.

Vacuum venting

Vacuum venting involves a vacuum pump that is attached to the venting channels and may be placed in a number of locations within the mold. This is highly efficient in eliminating trapped air and thus it can be used in large parts or complicated shapes.

Micro-venting

Micro-venting involves small venting channels, which are normally less than 0.0005 inches deep and can be installed in narrow crevices and thin walls. This process results in few or no visible marks on the part surface and is therefore useful in high precision parts and optical components where appearance is paramount.

Velve gate venting

Valve gate venting is a combination of venting and the gate operation, which enables it to vent at the first point of plastic entry, which may enhance the quality of the parts and also decrease the cycle time. Nonetheless, valve gate venting can only be applied to valve gate hot runners.

How Do You Determine the Correct Dimensions for Vents?

The cost of incorrect vent size is high. Too large in size and you have flash. Maker them too small you get burn marks. It is a guessing game but you always lose on the game and you end up wasting time and money on rework of molds. But what would you do to be able to compute the correct size in the first place?

The first thing in determining correct vent dimensions is the plastic material you are working with. The recommended depth of every material varies, and is usually between 0.01 mm and 0.05 mm. This depth is vital, it allows the air to escape and prevents the flow of the viscous plastic. The width of the vent must be large (minimum 5 mm) to give a clear passage. Its length is made of a shallow primary body and a deeper secondary channel that is made so that the air is able to reach the atmosphere freely.

The most important one is the vent depth. It is a very accurate gauge, depending on the viscosity of the plastic that you are molding. The material of low viscosity such as Nylon will need a very shallow vent compared to a high-viscosity material such as PVC. When the vent is excessively deep the fluid plastic will spill into the vent forming flash which must be cut off by hand, which increases labor expenses and results in waste. In case it is too shallow, the air will not be able to leave quickly, and the defects we have mentioned will occur. The data sheet provided by the material supplier has to be consulted in regards to their recommended vent depth. You do not guess it.

The Anatomy of a Vent Channel

A standard vent isn’t just one simple groove. It’s typically designed with two stages to work effectively.

-

Primary Vent (Vent Land): This is the shallowest part of the vent, located right at the edge of the mold cavity. Its depth is the critical dimension we just discussed. The length of this primary section is also important. If it’s too long, the air will have too much resistance to overcome. A good rule of thumb is a length between 1.0 mm and 2.5 mm.

-

Secondary Vent (Relief Channel): After the short primary section, the vent channel deepens significantly, often to 0.5 mm or more. This deeper channel creates a low-pressure path for the air to travel quickly to the outside atmosphere. This two-stage design ensures air is efficiently removed without building up back pressure.

Here is a quick reference table for common materials. Always confirm with your specific material supplier, but this gives you a starting point.

| Plastic Material | Recommended Vent Depth (mm) | Recommended Vent Depth (inch) |

|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene (PS) | 0.02 – 0.05 | 0.0008 – 0.002 |

| Polypropylene (PP) | 0.02 – 0.04 | 0.0008 – 0.0015 |

| Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS) | 0.02 – 0.04 | 0.0008 – 0.0015 |

| Polycarbonate (PC) | 0.03 – 0.06 | 0.0012 – 0.0024 |

| Nylon (PA6, PA66) | 0.01 – 0.03 | 0.0004 – 0.0012 |

| Acetal (POM) | 0.01 – 0.02 | 0.0004 – 0.0008 |

Getting these dimensions right from the beginning will save you from endless mold adjustments and troubleshooting down the line. I always tell my clients, "Measure twice, cut once" applies just as much to vent design as it does to any other part of mold making.

Best Practices for Injection Mold Venting Design

Optimal Injection Mold Venting Design.

Venting plays a very important role in the design of injection molds in order to produce quality products. Best practices must be adhered to in order to have effective venting of molds. The right size and location of the vent should be in accordance with certain plastic materials.

Ventilation is planned to avoid such problems as traps of gases and burns. The appropriate selection of the vent locations also reduces the defects that are visible on the final product surface. Venting designs should be in line with flow properties of various plastics.

The cooperation of a designer of molds and material experts improves the effectiveness of venting. The collaboration enables the provision of viable solutions that suit special project requirements. Venting considerations included at the design stage will save on expensive redesigns at a later stage.

Optimize venting design using a checklist:

- Measure plastic flow characteristics.

- Identify optimal location and vent size.

- Focus on strategic vent locations.

- Co-operate with material specialists.

- Include venting requirements at the design stage.

The implementation of these best practices results in a better performance of mould. They assist in checking the quality of parts and their timely production. The design of venting is planned thoroughly, which improves efficiency and product results.

Where Are the Best Locations to Place Vents in a Mold?

You have made your vents of the appropriate size, however, when you install them on the inappropriate location, they become absolutely useless. Air will not be trapped and you will be left with your head bent in bewilderment as to why you still have parts that are malfunctioning. It is a widespread and irritating issue. The trick lies in anticipating the direction the air is going to and providing it with a way out at the point.

Vents are to be mostly located at the end of material fill in the mold cavity. It is here that the air is pushed and trapped automatically as the plastic moves on. It should also be provided with vents to any local high points, ribs or deep pockets where the air can be trapped. These final fill locations and air traps can only be predicted using the mold flow simulation software as the most accurate method of ensuring effective vent locations.

The number one rule for vent location is to place them where the part fills last. As the molten plastic flows from the gate and fills the cavity, it pushes the air ahead of it. This air gets cornered at the point furthest from the gate. If there’s no vent there, the air has nowhere to go. Back in the day, we relied on experience and a bit of guesswork to find these spots. We would do a "short shot" test, injecting just enough plastic to partially fill the cavity, to see the flow pattern and predict the last fill point.

Using Technology for Precision

A much better tool is available today, mold flow simulation. This computer program enables us to computerize the process of injection before any piece of steel is cut. It not only tells us the way the plastic will flow, in which places we will have the weld lines, but, probably and most importantly, where the last fill points and possible air traps will be. I would never leave out a flow analysis of a new or complex part. The low initial investment would save tens of thousands in rework of molds and production time loss. It removes all the guesswork.

Key Locations for Venting

Besides the last point of fill, there are other common areas that almost always need venting.

- Weld Lines: When two plastic flow fronts meet, they trap a line of air between them. This creates a weak spot known as a weld line or knit line. Placing a vent directly on this line allows the trapped air to escape, resulting in a much stronger bond.

- Deep Ribs and Bosses: Air can easily get trapped at the top of tall, thin features like ribs or screw bosses. The plastic flows up both sides and traps a pocket of air at the very end. Venting these specific features is often necessary.

- Parting Line: The easiest place to add a vent is on the parting line of the mold—the surface where the two halves meet. For most parts, it’s recommended to have vents around at least 30% of the parting line perimeter.

I once worked on a case for a handheld scanner. It had a deep battery compartment that consistently showed burn marks at the bottom. The main parting line was fully vented, but the team overlooked this deep, isolated pocket. By adding a small vent pin at the bottom of that compartment, the problem was solved completely. This experience taught me to think in three dimensions and hunt for every possible air trap.

What Are the Different Vent Configurations and When Should You Use Them?

You understand where to locate vents and what they are supposed to be, but what are they supposed to look like? It is not always possible or effective just to cut a simple channel on the parting line, particularly when the part geometry is complicated. The inappropriate type of vent can be as bad as having no vent at all resulting in constant defects.

A parting line vent is the most popular type of vent; it is used in simple parts, where the air is confined in the split line of the mold. Where air is present in the cavity, and remote to the parting line, ejector pin vents or special vent pins are to be used. Porous mold inserts are an upscale product that is used in areas with a high level of care where traditional vents cannot be used so the gas is released in the steel itself.

The type of vent you choose depends entirely on where the air is getting trapped. Your part’s geometry dictates the best solution. In my experience, a combination of different vent types is often needed for complex molds. Let’s look at the main options and when they are the best choice.

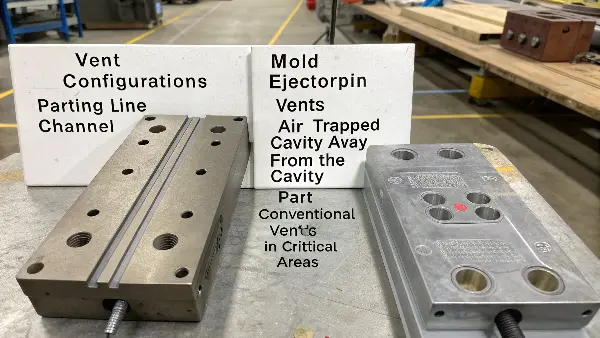

Standard Venting Configurations

-

Parting Line Vents: This is the simplest and most common method. A shallow channel is machined directly onto the parting line of one half of the mold. It’s easy to create and maintain. This configuration is perfect for venting the general perimeter of a part and is the first choice whenever the air trap is located on the parting line itself.

-

Ejector Pin Vents: What if air is trapped in the middle of the part, far from the parting line? An ejector pin, which is already needed to push the part out of the mold, can double as a vent. By grinding small flats (typically 0.02-0.04 mm deep) on the sides of the pin, you create a perfect escape route for trapped air. This is an incredibly efficient and common way to vent areas around bosses or core details.

-

Dedicated Vent Pins: Sometimes, there is an air trap where you don’t have an ejector pin. In this case, you can add a dedicated pin just for venting. It looks like an ejector pin but its sole purpose is to provide an escape path. It’s a targeted solution for very specific problem areas.

Advanced and Specialized Venting Solutions

Sometimes, conventional methods just aren’t enough, especially with high-gloss finishes or gas-sensitive materials.

| Vent Type | Best Use Case | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parting Line Vent | Perimeter of the part | Simple, low-cost, easy to maintain | Only works on the parting line |

| Ejector Pin Vent | Internal features, bosses, cores | Utilizes existing components, cost-effective | Limited to ejector pin locations |

| Dedicated Vent Pin | Specific, isolated internal air traps | Precise, targeted venting | Adds complexity and cost to the mold |

| Porous Inserts | High-aesthetic surfaces, deep ribs | Excellent venting, eliminates burn marks | High cost, can clog over time |

I remember a project for a medical device with a mirror-finish surface. Any tiny imperfection was cause for rejection. We couldn’t use pin vents because they would leave a circular mark. The solution was to use a small insert made of porous steel right at the last fill point. The gas escaped directly through the microscopic pores in the steel, leaving a perfectly flawless surface. While expensive, it was the only way to meet the client’s stringent quality requirements. Choosing the right configuration is about finding the most effective tool for the specific problem you’re facing.

Conclusion

Learning how to vent molds has nothing to do with a secret formula, but rather it should be systematically applied through proven principles. With a little thought of the correct dimensions of the material you are going to use, where exactly the air is trapped, and the best arrangement of the vents to use in your part geometry you can help remove an enormous selection of the most common molding defects. This information will make venting your operations a source of problems and a potent tool to accomplish quality, efficiency, and profitability.