Do you have a problem of injection molding such as burn, short shots, or weak weld lines? It could be the machine or the material but the actual offender is usually lurking in the shadow. The problems result in delays during production and wastage of materials which are going to eat into your profits and frustrate you. The trick is to realize that vent design that is successful on one plastic may be a complete failure on another.

This, yes, the proper venting is very much specific on the plastic material that one uses. The viscosity, melt flow rate, and profile of gas emissions of each polymer have a special influence on the optimal vent depth and position. As an illustration, in low-viscosity materials such as Nylon the vents must be very shallow (in the range of 0.012-0.025 mm) to avoid flash, whereas rigid PVC which may release corrosive gases must have large vents made of corrosion-resistant steel. These material-specific requirements need to be mastered to ensure consistency and high quality production and prevent the expensive damage of molds.

You see, getting venting wrong can ruin a perfectly good mold and an entire production run. It’s a detail that separates the amateurs from the pros. But it’s not black magic. It’s a science based on how different materials behave under pressure and heat. In my years in this business, I’ve seen countless projects saved by focusing on this single detail. In this guide, I’ll walk you through the specifics for over 20 common plastics. Let’s break down why this is so important for your success.

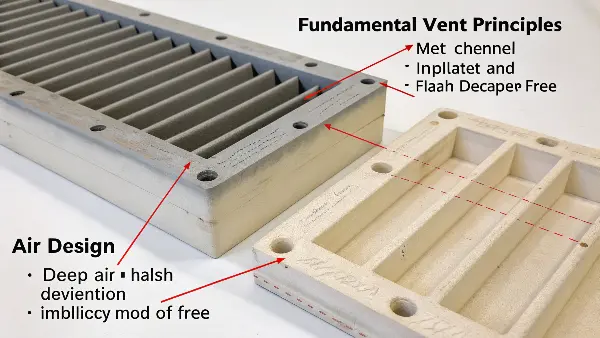

What Are the Fundamental Principles of Vent Design?

Do you think that you are guessing where to put vents in your molds? You can put in a couple on the parting line and wish to luck and only to discover that you still have a problem. This is a trial and error method which is not efficient. It may cause costly moulding adjustments and deadline failure, simply due to the fact the fundamental air flow principles were not observed. You must not depend on guesswork, you must have a reliable strategy.

The principle behind this is to establish an easy way out of air and gas whilst preventing the molten plastic. The last points should be filled with vents and where the lines of the welds occur since they are the areas where airtightness can occur through traps. They should also be deep enough so as to allow gas to escape rapidly and at the same time should be shallow enough to ensure that the material does not flash. An ordinary vent has a shallow land area and a higher relief area to make sure that the air can escape out of the block of the mold fully.

Let’s dig into the core mechanics. A good vent system has three key parts. First is the vent location. You must place vents at the absolute end of the flow path. Think of filling a bottle with water; you need to leave a space for the air to get out. It’s the same in a mold. I always use mold flow analysis to pinpoint these "last-to-fill" areas accurately. Weld lines are another critical spot, as two melt fronts trap air when they meet. Second is the vent depth and land. The depth is the most critical dimension and is entirely material-dependent, which we’ll cover extensively. The land is the short, shallow section (usually 1-5 mm long) that freezes the plastic before it flashes. If the land is too long, the gas can’t escape effectively. Third is the relief channel. This is a deeper channel (0.5-1.5 mm deep) cut behind the land. Its job is to collect the gas from the shallow vent land and transport it out of the mold entirely. Without a proper relief channel, the air has nowhere to go, and the vent becomes useless.

How important is Mold Design?

The construction of the mold vents is also important in guaranteeing good ventilation of gases. A prudent choice of the vent placement will assist in the realization of the optimal airflow and the reduction of defects. Avoiding poor moulding can be enhanced in strategic vent site positions.

Another necessary consideration with regard to design of the mould is the vent size. Smaller vents can also fail to carry away a sufficient amount of gases resulting to defects. On the other hand, when too large in size, vents will lead to material spillage and molds. The difficulty is to balance the right way.

The vents applied in designing the mould have different kinds with their purposes:

- Edge Vents: This is located at the edge of the mold to release the gas fast.

- Flash Vents: Vents that are slim, and through which the gas escapes without loss of material.

- Pin Vents: Small openings that get rid of trapped air in in-depth cavities.

These features can be analyzed in designing a mold and this will improve the efficiency in manufacturing. The knowledge of the operation of each type of vent allows the engineers to develop molds that can ensure the quality of the product, as well as a speedy production process. Constant improvements can be achieved through constant evaluation and modification of the design.

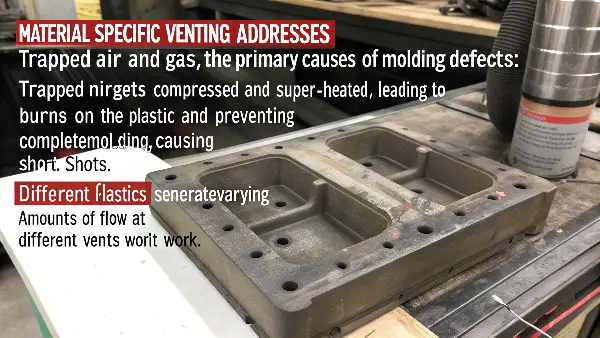

Why Is Material-Specific Venting So Crucial for Part Quality?

Ever wonder why a mold that ran perfectly yesterday is suddenly producing scrap parts with a new material? You might see burn marks at the end of the fill path or parts that aren’t fully formed. It’s frustrating because it feels like a random problem, but it’s not. This inconsistency directly impacts your bottom line, causing delays and forcing you to troubleshoot under pressure, never knowing when the problem will strike again.

Material-specific venting is important, as it was made to address the trapped air and gas directly, which are the most common causes of many molding defects. The air trapped in the cavity compresses and gets superheated, causing diesel-like burn marks on the plastic. It also creates back pressure that prevents the mold from filling completely, resulting in short shots. Different plastics generate different amounts of gas and flow at different rates, so the "one-size-fits-all" vent will either be too big, causing flash, or too small, which traps the air and compromises part integrity and appearance.

Let’s dive deeper into the physics. The plastic melt that enters the mold acts like a piston, pushing the air already in the mold ahead. If that air can’t escape through vents, it gets compressed into the last corner of the cavity. This happens so fast that the temperature of the air goes through the roof, often exceeding the ignition point of the plastic. This phenomenon is called the "diesel effect," and it burns the plastic, leaving black or brown burn marks. I’ve even seen this ruin many an expensive mold. Besides burns, this entrapped air then acts as a cushion. The injection pressure coming from the machine has to fight against this air pressure. If that air pressure is too high, then plastic melt stops before it fills the cavity and results in incomplete parts-or "short shots." Every material has a different viscosity. A low-viscosity material such as Nylon flows easily and will slip into vents if they are too deep and cause flash. A high-viscosity material such as PC moves slower and needs deeper vents to give enough time for all air to escape. And that is why you simply cannot use the same design for vents with different materials and expect professional results.

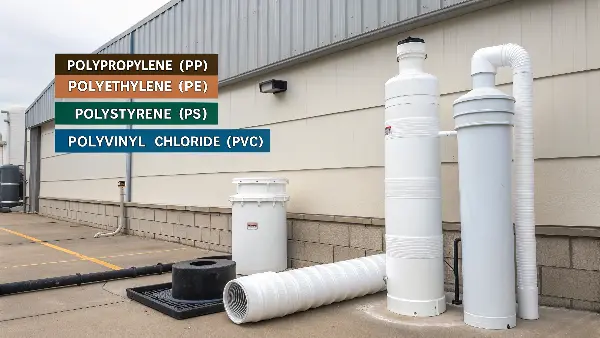

How Do Venting Needs Vary for Common Commodity Plastics?

Are you working with everyday plastics like Polypropylene (PP) or Polyethylene (PE) and still getting inconsistent results? You might think these "easy" materials don’t need much attention to detail. But this assumption can lead to subtle defects like poor surface finish or weak parts that you only discover later. This can damage your reputation with customers who expect reliable quality, even with low-cost materials. It’s a problem that can quietly cost you a lot of money.

Commodity plastics have distinct venting needs based on their flow properties. Low-viscosity PE and PP are prone to flash, so they require shallower vents. Polystyrene (PS) is more rigid and can benefit from slightly deeper vents for better filling. Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) is unique as it releases corrosive gases when heated, so its vents must not only be properly sized but also made from corrosion-resistant steel to prevent mold degradation over time. Ignoring these differences leads directly to defects.

Let’s break down the most common plastics I see every day. These materials are the workhorses of our industry, so getting them right is critical. I always refer to a chart, but over the years, these numbers become second nature. For these materials, the game is about balancing flow rate against flash risk. Keep in mind these are starting points; your specific grade of material and mold design may require adjustments.

| Material | Common Vent Depth (mm) | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Polypropylene (PP) | 0.02 – 0.04 | Very fluid, highly prone to flash. Start with tighter vents. |

| Polyethylene (PE-LD/HD) | 0.02 – 0.05 | Similar to PP, flows very easily. Watch out for flash. |

| Polystyrene (PS) | 0.02 – 0.05 | Fills easily. Good venting prevents flow lines and improves finish. |

| High Impact PS (HIPS) | 0.025 – 0.05 | Slightly more viscous than general-purpose PS. |

| Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) | 0.02 – 0.04 | Critical: Releases corrosive HCl gas. Vents MUST be made of stainless or plated steel. |

| SAN (Styrene Acrylonitrile) | 0.02 – 0.05 | Good dimensional stability, vents help maintain it. |

With PP and PE, my primary concern is always flash. I tell my team to start on the lower end of the vent depth range and only open it up if we see signs of trapping. For PVC, the material itself is the biggest hazard. I once saw a client ruin a brand new P20 steel mold in a week because they ran PVC without realizing their vents would corrode. We had to remake the inserts with stainless steel. It was a costly lesson in material science.

The importance of Mold Venting and Impact of Various Plastics on Mold Venting Requirements

Venting injection molding is crucial in producing molded components of high quality. In its absence, gases trapped may produce serious flaws in the end product. Such flaws may contribute to the rise of costs and delays in production.

The mold has vents so that gases can escape when molding. This eliminates such frequent problems as voids and surface blemishes. Venting of each plastic material is different.

There is a reason why venting is important, which will be considered as follows:

- Reduces product defects

- Efforts better filling and cycle time.

- Improves the quality of the products

With venting issues focused on, manufacturers will be able to have more reliable operations.

The Impact of Various Plastics on Mold Venting Requirements

The distinct characteristics of various plastic materials influence the need for venting. For example, larger or more vents are frequently needed for high-viscosity plastics. This is because, in contrast to materials with low viscosity, they flow less readily.

The behavior of thermosets and thermoplastics during molding differs greatly. Because of their smooth flow properties, thermoplastics usually require less venting. For best results, thermosets may need more complex venting configurations.

The particular plastic material utilized should be taken into account while developing mold venting systems. A one-size-fits-all strategy may result in flaws and inefficiencies in production.

Important variations in plastic include:

- Levels of viscosity

- Sensitivity to heat

- Production of gas during molding

Higher production quality and efficiency are ensured by adapting mold venting to the plastic type.

Do Engineering Plastics Like PC, ABS, and Nylon Require Special Venting?

Are you moving from commodity plastics to engineering-grade materials like ABS or PC? You might be expecting better performance but instead are facing new challenges like splay marks or inconsistent gloss levels. These high-performance materials are less forgiving. A vent design that was "good enough" for PP will almost certainly fail with Nylon or PC, leading to frustrating delays and parts that don’t meet spec. This can stall your project and make you question the material choice itself.

Yes, engineering plastics do require much more precise venting because of their properties. Amorphous materials such as ABS and PC are hygroscopic (absorb moisture), which releases steam that must be vented along with air. Crystalline materials like Nylon and Acetal are very low in viscosity when melted and therefore are very prone to flash. They require some of the tightest, most precise vents in the industry for a good process window. Each family is different, requiring its own unique approach.

Engineering plastics are chosen for their superior properties, and proper venting is key to achieving them. When I design a mold for these materials, my checklist is much more rigorous. Moisture is a huge factor. Materials like PC, ABS, and Nylon must be dried properly before molding. If they are not, the moisture turns to steam in the barrel, and that steam must be vented from the mold. This extra gas volume means you need excellent venting efficiency. The biggest challenge, however, is the difference in viscosity.

| Material | Common Vent Depth (mm) | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| ABS | 0.025 – 0.05 | Prone to burn marks and poor gloss without good venting. Needs proper drying. |

| Polycarbonate (PC) | 0.04 – 0.08 | High viscosity, needs deeper vents. Must be VERY dry to prevent splay. |

| PC/ABS Alloy | 0.03 – 0.06 | A blend of properties. Venting sits between PC and ABS. |

| Nylon (PA6, PA66) | 0.012 – 0.025 | Critical: Extremely low viscosity. Needs very shallow, tight vents to prevent flash. |

| Acetal (POM) | 0.012 – 0.025 | Similar to Nylon. Very fluid and requires tight vents. Prone to gas burns. |

| Acrylic (PMMA) | 0.04 – 0.08 | Brittle and prone to crazing if fill pressure is too high due to poor venting. |

| Polyester (PET, PBT) | 0.015 – 0.03 | Low viscosity, especially when glass-filled. Requires tight vents. |

The first time I molded Nylon, I learned a hard lesson. We used a standard 0.05 mm vent depth that worked for ABS. The result was flash everywhere. The material was so fluid it shot right through the vents. We had to weld the vents shut and re-machine them to just 0.02 mm. It was a perfect example of how materials that seem similar can behave completely differently. For PC, the opposite is true. It’s thick like molasses, so you need deeper vents to help it push the air out. Getting these right is not optional; it’s fundamental to success.

What Are the Venting Challenges with High-Performance Plastics?

Are you venturing into the world of high-temperature, high-performance plastics like PEEK or LCP? These materials offer incredible strength and thermal resistance, but they come with a steep learning curve. The processing window is narrow, and the raw material is expensive. Any mistake, especially with venting, can lead to scrapped parts that cost a fortune and potentially damage very expensive, hardened steel tooling. It’s a high-stakes game where precision is everything.

High-performance plastics present unique venting challenges due to their extreme processing temperatures and unique flow characteristics. Materials like PEEK and PSU are molded at very high temperatures, which makes any trapped air even more likely to cause severe burn marks. Liquid Crystal Polymer (LCP) is extremely low-viscosity and requires exceptionally tight and precise vents, similar to Nylon but even more critical. Standard venting practices are often inadequate for these demanding materials.

Working with high-performance plastics is like being a surgeon. There is no room for error. The mold temperatures can exceed 200°C (392°F), and melt temperatures can push 400°C (752°F). At these temperatures, any imperfection in the process is magnified. Venting is your number one tool for ensuring stability. We are not simply talking about vent depth for these materials but about the whole system. That is why we often use porous mold inserts or vacuum venting to actively pull air and gas out of the cavity when passive venting is not enough.

| Material | Common Vent Depth (mm) | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| PEEK | 0.015 – 0.03 | High temp & cost. Defects are unacceptable. Requires perfect venting. |

| PSU / PES / PPSU | 0.02 – 0.05 | High temp amorphous materials. Need excellent venting to avoid burns. |

| LCP (Liquid Crystal Polymer) | 0.005 – 0.015 | Critical: Extremely fluid, almost water-like. Needs the tightest vents. |

| PPS | 0.015 – 0.025 | Very fluid when filled with glass. Can be abrasive, requires hardened steel. |

| PEI (Ultem) | 0.025 – 0.05 | High-temp amorphous. Excellent venting is needed for optical clarity and strength. |

| TPE / TPU | 0.01 – 0.025 | Very soft and flexible. Prone to flash, needs very shallow vents. |

I remember a medical project using LCP for a tiny, complex connector. The client was experiencing short shots despite maxing out the injection pressure. Normal vents were flashing even at 0.02 mm. The solution was to machine vents at only 0.01 mm depth—the thickness of a piece of foil. It required incredibly precise machining, but it was the only way to get the part to fill without flash. For these materials, you can’t just be a mold maker; you have to be a specialist who understands the extreme behavior of these polymers.

How Can You Diagnose and Fix Venting-Related Mold Defects?

Are you tired of playing the guessing game when a molding defect appears? Is it the temperature, the pressure, or the material? When production stops, the pressure is on to find a solution fast. Randomly tweaking parameters without a clear diagnosis can make things worse and waste hours of valuable time. Knowing how to quickly identify a venting problem is a skill that can save a project and make you look like a hero.

You can diagnose venting problems by looking for specific visual cues on the part. Burn marks at the end of the fill path are a classic sign of trapped, super-heated air. Short shots or incomplete parts point to back pressure from unvented air fighting the plastic flow. Poor surface finish, weak weld lines, and even warp can also be caused by inadequate venting. The location of the defect is your biggest clue to where a vent is needed or needs to be improved.

Over my career, I’ve developed a simple but effective diagnostic method. First, identify the defect. Is it a burn mark? A short shot? A sink mark? Second, locate the defect on the part. Where is it happening? Almost always, the location tells you the story. For example, if you see a burn mark, you know that’s the last place the air had to go. That exact spot needs a vent or a better vent. If you have a short shot, find where the flow stopped. The air ahead of that point couldn’t get out.

Here’s my quick troubleshooting guide:

- Burn Marks: The most obvious sign. You have trapped air. Solution: Add a vent at the exact location of the burn. If a vent is already there, it’s too shallow, too long, or clogged. Clean it and measure it. If needed, deepen it slightly (in 0.01 mm increments).

- Short Shots: The mold isn’t filling completely. Solution: Check venting at the short shot location. Also, check vents along the entire parting line. Poor perimeter venting can create general back pressure.

- Flash: Plastic is escaping the cavity. Solution: Your vent is too deep for the material’s viscosity. The mold might also be clamping unevenly. Measure the vent depth; it likely needs to be made shallower (by welding and re-machining).

- Weak Weld Lines: Two flow fronts meet but don’t fuse properly. Solution: Air is trapped at the weld line, preventing a strong bond. Add an overflow tab or a vent directly on the weld line to let the trapped gas escape.

- Dieseling/Clogging: Vents get blocked with residue over time. Solution: Institute a regular mold cleaning and maintenance schedule. I tell my clients to clean vents every 4-8 hours of production for critical jobs. This preventative step saves a lot of trouble later.

Conclusion

Mastering injection mold venting isn’t about memorizing a single number; it’s about understanding the unique personality of each plastic. From the easy flow of PP to the extreme fluidity of LCP, every material demands a specific vent design. By tailoring your vents to the material, you move from guesswork to precision, eliminating defects, protecting your tooling, and ensuring consistent, high-quality results. This knowledge is a cornerstone of successful and profitable molding.