The secret is to learn how to translate your needs into precise engineering specifications. If you have a great idea for a plastic part but your manufacturing partner keeps asking technical questions you can’t answer, this communication gap will cause delays, misunderstandings, and prototypes that don’t match your vision.

Translating customer requirements into engineering specifications involves converting customer needs, like "it should be durable," into measurable technical parameters. This could mean defining a specific material like Polycarbonate, a wall thickness of 3mm, and a performance standard like passing a drop test from 1.5 meters. This structured process ensures the final plastic part’s design and function align perfectly with the initial customer vision. It is a critical step for preventing costly errors and guaranteeing manufacturing success.

This seems straightforward, but the details make all the difference. I’ve seen projects get derailed because a single requirement was misinterpreted. So, how do we get this right every single time? Let’s break down the fundamental concepts first to build a solid foundation. Understanding the core differences between what a customer wants and what an engineer needs to know is the first step toward mastering this process.

What is the difference between Customer Requirements and Rngineering Specifications?

Have you ever described exactly what you wanted, only for the technical team to come back with something completely different? It feels like you’re speaking separate languages. They talk about tolerances and material grades, while you’re focused on user experience and appearance. This disconnect is a common source of friction in product development. But understanding their distinct roles is the solution.

Customer requirements are qualitative descriptions of what a product should do from a user’s perspective, using everyday language like "it should be easy to hold." In contrast, engineering specifications are quantitative, measurable, and technical details that define how to achieve those requirements. They use precise engineering language, listing dimensions, materials, tolerances, and performance standards (e.g., "ergonomic grip section with a diameter of 30mm ±0.5mm, made from TPE material").

Let’s dive deeper into this distinction, as it is the foundation of any successful manufacturing project. Getting this right from the start saves an incredible amount of time and money. I remember a client, let’s call him Michael, who wanted a new casing for a handheld scanner. His requirements were clear from his point of view, but they needed translation.

The Voice of the Customer (VOC)

The Voice of the Customer is the "what." It’s about the feeling, function, and purpose of the part from the end-user’s perspective. For Michael’s scanner casing, his requirements were:

- "It needs to be tough enough for a warehouse environment."

- "It can’t be too heavy for someone to carry all day."

- "It should look modern and professional."

- "It must be easy for our technicians to open for service."

These are all valid and essential points. They define whether the product will be a success in the market. However, I can’t input "tough enough" into a CNC machine or an injection molding press. This is where the translation begins.

The Voice of the Engineer (VOE)

The engineer’s voice is the "how." As manufacturers, it is our responsibility to translate the volatile organic compound (VOC) into a tangible, technical language that is comprehensible to machinery and quality control procedures. We take each of Michael’s points and give them quantifiable values. The engineering specification is created from this.

The table below shows how we translated his needs:

| Customer Requirement (The "What") | Engineering Specification (The "How") |

|---|---|

| "Tough enough for a warehouse environment." | Material: PC/ABS blend. Performance: Must withstand a 1.5-meter drop test onto concrete without cracking. |

| "Can’t be too heavy." | Part Weight: Maximum of 150 grams. Wall Thickness: Nominal 2.0mm. |

| "Look modern and professional." | Finish: MT-11010 light bead blast texture. Color: Pantone Cool Gray 9 C. Parting lines must be minimized. |

| "Easy to open for service." | Assembly: Use four M3 screw inserts. Design with snap-fits that allow for 10+ open/close cycles without failure. |

By building this bridge, both Michael and my team had a clear, shared understanding. There was no ambiguity. He knew what he was getting, and we knew exactly what to build. This process eliminates guesswork and ensures the final product truly meets the customer’s intent.

How Do You Convert Vague Customer Needs into Measurable Technical Parameters?

The process of transforming general customer comments into engineering specifications calls for disassembling general comments into special criteria. The word "strong," "lightweight," and "high quality" are meaningless in engineering terms until they are quantified. The challenge is to move from perception to performance.

This starts with the formulation of clarification questions that revolve around practical usage. For instance, “strong” could mean resistance to impact, weight-carrying capabilities, and fatigue resistance. Depending on the requirement and meaning derived for this requirement, different variables will be involved, such as impact resistance (in Joules), maximum possible deflection (in mm), and number of cycles (until the part fails). Then the requirement for a “lightweight” part will be converted into a maximum weight for the part or maximum material density.

These parameters, once clarified, have numerical values assigned to them by way of targets and acceptance criteria. Test procedures also have to be specified. This would include drop tests, tensile tests, or environmental tests. This would make sure all parameters have a definitive pass/fail situation. In doing so, all expectations get clarified, and there is a common understanding of success on both parts – customer and supplier.

How Do You Prioritize Conflicting Customer Requirements During Design?

In the development of plastic parts, customers frequently have conflicting demands, particularly when they want high strength, low cost, light weight, and premium appearance all at once. Setting priorities is crucial to avoiding over-engineering or impractical designs.

Prioritizing requirements according to product function, safety, and business impact is the first step. Safety, regulatory compliance, and core performance requirements always come first. After primary constraints are met, secondary requirements—like appearance or weight optimization—are taken care of.

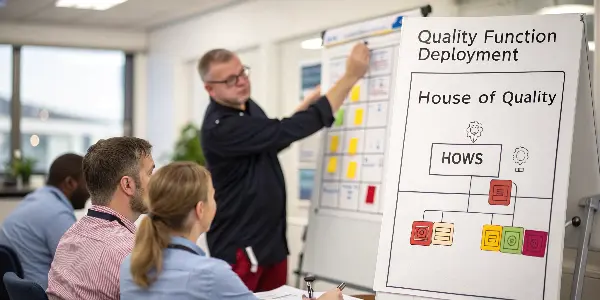

By giving customer needs importance weights and connecting them to engineering features, structured tools like Quality Function Deployment (QFD) aid in conflict resolution. Trade-offs become apparent as a result. For instance, thicker walls may be stronger, but they also weigh more and take longer to cycle. Seeing these connections enables well-informed choices as opposed to arbitrary concessions.

Maintaining consistency in design choices throughout development is ensured by well-documented priorities. In order to minimize disagreements and avoid late-stage redesigns, trade-offs are made consciously and openly when they are required.

What is the engineering requirement spec?

You’ve translated customer needs into technical terms, but where do all these details live? Piling them into emails or notes creates chaos and increases the risk of mistakes. A disorganized list of specifications is almost as bad as having none at all. You need a single, reliable document that everyone on the project can turn to for answers. This is where a formal specification document becomes essential.

An engineering requirement specification, often called a spec sheet or technical specification, is the formal document that contains all the quantitative technical data for a product or part. It is the master blueprint that guides design, manufacturing, and quality control. This document details everything from dimensions, materials, and tolerances to performance standards, aesthetic finishes, and regulatory compliance. It serves as the single source of truth for the entire engineering and production team.

Creating a comprehensive engineering requirement spec is not just about listing numbers; it’s about building a complete guide for your project. A well-structured spec sheet is the most powerful tool you have for ensuring consistency and quality. It’s what I insist on before we even start designing a mold. It protects both the client and us from costly assumptions.

Key Components of a Spec Sheet for Engineering Specifications

A thorough spec sheet for a plastic part should be organized and unambiguous. While the specifics vary by project, here are the core sections that should almost always be included. Think of it as a checklist to ensure nothing is missed.

- Part Information: This includes the part name, part number, revision number, and the project it belongs to. It is the basic identification.

- Material Specifications: Clearly define the plastic resin to be used (e.g., Polypropylene, Homo PP), the specific grade (e.g., Sabic 575P), and any required additives like colorants (e.g., Pantone 286 C) or UV stabilizers.

- Dimensional & Geometric Tolerances: This is where your 3D CAD model is supported by details. It lists critical dimensions and the acceptable range of variation (tolerances). It also references the geometric dimensioning and tolerancing (GD&T) standards to control the form, orientation, and location of features.

- Performance Requirements: This section answers the question, "What must the part do?" It includes mechanical requirements (e.g., tensile strength), environmental resistance (e.g., operating temperature range from -20°C to 80°C), and lifecycle expectations (e.g., must withstand 5,000 cycles of use).

- Aesthetic & Finish Requirements: How should the part look and feel? Specify the desired surface texture (e.g., SPI-A2 high polish or VDI 3400 Ref 27 texture), color consistency standards, and define "cosmetic surfaces" where blemishes like sink marks or flash are unacceptable.

- Regulatory & Compliance Standards: If the part is for a specific industry, like medical or food service, this section is crucial. It lists required certifications, such as FDA compliance for food-contact materials or RoHS compliance for electronics.

By meticulously filling out each of these sections, you create a document that leaves no room for error. It becomes the contract between the client’s vision and the manufacturer’s execution.

What describes a method for translating customer requirements into functional design?

So you understand the difference between customer needs and engineering specs. But how do you perform the translation systematically? Simply making a list isn’t enough, especially for complex products where one requirement can conflict with another. You need a structured method to ensure all customer needs are captured, prioritized, and correctly translated into technical features, preventing critical details from being overlooked.

Quality Function Deployment (QFD) is a structured methodology for translating customer requirements into functional design specifications. Often called the "House of Quality," this method uses a matrix to visually map the relationship between customer wants (the "Whats") and engineering characteristics (the "Hows"). It helps teams prioritize efforts, identify potential trade-offs, and ensure that the final design is driven directly by the voice of the customer. It’s a powerful tool for cross-functional collaboration.

The QFD process might look complex at first, but it’s a very logical tool that I’ve used to help clients clarify their own priorities. By working through it, we can make sure that our engineering efforts are focused on what truly matters to the end user. It prevents us from over-engineering a feature the customer doesn’t care about, or worse, under-engineering one they consider essential.

Building the House of Quality

The "House of Quality" is the most famous tool within the QFD framework. It gets its name from its shape, which looks like a house with a "roof." Let’s break down its primary sections step-by-step.

-

Customer Requirements (The "Whats"): This is the left wall of the house. Here, you list all the customer needs you gathered. You also include a column for the customer importance rating (e.g., on a scale of 1 to 5). For Michael’s scanner, "toughness" might be a 5, while "looks modern" might be a 3.

-

Technical Descriptors (The "Hows"): This forms the ceiling of the house. This is where you list the measurable engineering characteristics that correspond to the customer requirements. For "toughness," the technical descriptors could be "impact strength (Joules)" and "material hardness (Rockwell)."

-

Relationship Matrix: This is the main body of the house. It’s a grid where you evaluate the strength of the relationship between each customer requirement and each technical descriptor. You use symbols to denote a strong, medium, or weak relationship. Does increasing impact strength have a strong effect on perceived "toughness"? Yes. You mark that intersection accordingly.

-

Technical Correlation Matrix (The "Roof"): The triangular roof of the house shows the interrelationship between the technical descriptors themselves. For example, selecting a harder material (increasing Rockwell hardness) might positively correlate with higher impact strength. But it might negatively correlate with weight, creating a trade-off that needs to be balanced.

-

Technical Priorities & Targets: The bottom of the house serves as the foundation. Here, you calculate the importance of each technical descriptor based on the customer ratings and the relationship matrix. This gives you a ranked list of engineering priorities. You then set specific target values for the most important metrics (e.g., "Target Impact Strength: >5.0 Joules").

This process forces a team to have critical conversations and make data-driven decisions, ensuring the final design is a direct reflection of customer desires.

What is the role of Prototypes and Testing in Proving Engineering Specifications?

Prototyping and experimentation represent an interface between the theoretical specification and the actual performance. Even engineering specs that are well-defined should be tested in real operating conditions in order to ensure that assumptions are right.

Early testing of form, fit and functionality is made possible through prototyping. Early prototypes can be made with the help of 3D printing or soft tooling to check size, ergonomics, and fit. Models in later stages with production-intent materials and processes confirm mechanical strength, surface finish, and durability.

Testing will determine the compliance of engineering specifications. This involves mechanical testing, environmental testing, lifecycle testing and assembly testing. Test failures are good since they tell of the weak points before mass production. Modifications here are much less expensive than those of hardened steel molds.

With the incorporation of prototyping and testing in the process of specification, risks are minimized, confidence is boosted, and the final product goes into production with an expected quality.

What is the role of the engineering specifications in minimizing the risks and costs of manufacturing?

Defined engineering specifications lower the risk of manufacturing since the ambiguity is removed. The results are fewer chances of interpreting, mistakes or guesses when the materials, dimensions, tolerances and performance requirements are clearly defined during production.

Cost wise, perfect specs avoid the unwarranted over-tolerance which complicates tooling and raises rejection levels. They also lessen the chances of mold rework which is among the most costly and time consuming corrections in the manufacture of plastics. Specification helps the suppliers to quote correctly, design tooling to optimize, and to plan out stable production processes.

Also, good specifications will enable quality control by offering practical acceptance thresholds. Inspection of parts can occur at a regular rate, faults are detected in early stages and corrective measures are implemented before a big quantity of parts is made. In the long run, it will result in increased output, reduced scrap, and consistent cost of production.

Essentially, engineering specifications are a risk-control system and they bring design purpose, manufacturing implementation and quality control into one, trustworthy system.

Why is this translation process so critical for project success?

Formal translation and documentation may seem like a tremendous amount of extra work to you. Why not just start talking and working on the design? Many startups and smaller businesses attempt this in an attempt to move more quickly, but it frequently results in more serious issues later on. One of the most frequent causes of project failure, budget overruns, and strained relationships with manufacturing partners is skipping this important translation step.

This translation process is essential because it removes uncertainty and establishes a common, quantifiable definition of success for all parties. By identifying misunderstandings before manufacturing starts, it avoids expensive rework. A precise set of engineering specifications guarantees that the finished product will not only operate as intended but also precisely match the customer’s vision and quality standards. It is the foundation of an efficient, predictable, and successful manufacturing outcome. Without it, you are simply guessing.

Getting the technical details right is only one aspect of this process’s significance. It increases confidence, simplifies processes, and eventually safeguards your investment. I have witnessed this numerous times. The best insurance policy you can have is a little more time spent on project definition at the beginning.

The True Cost of Miscommunication

When customer needs and engineering specs are not aligned, the consequences can be severe. This is not just a theoretical risk; it has real-world costs.

-

Infinite Design Revisions: The design team is essentially guessing if they are working from ambiguous requirements. This results in a cycle where a prototype is shown, criticism is given that it’s "not quite right," and the process is repeated. Time and money are spent on each revision. Because their straightforward request for a "strong clip" was never converted into a precise pull-force requirement, I once worked with a client who had gone through five revisions with another supplier. The first prototype was accepted after we defined it in thirty minutes.

-

Incorrect Mold Tooling: This is the biggest and most expensive risk. A steel injection mold is built to exact specifications. If those specifications are wrong, the mold is wrong. Modifying a complex steel mold is incredibly difficult and expensive, and sometimes, it’s impossible. A new mold can mean a delay of months and costs of tens of thousands of dollars, all because a requirement was not properly translated.

-

Failed Products and Recalls: If a critical performance or safety requirement is missed, the product might fail in the field. This can lead to anything from bad customer reviews to a full-blown product recall. Imagine a medical device component failing because the requirement "must be sterilizable" was not translated into a specific material choice that could withstand autoclave temperatures. The damage to both the budget and the brand’s reputation would be immense.

This translation process isn’t just paperwork. It is the primary risk-management tool in product development. It aligns the business goals (customer satisfaction) with the engineering actions (manufacturing execution). It turns a subjective idea into an objective, achievable reality.

Conclusion

The most crucial stage in product development is converting what a customer wants into a technical language that an engineer can create. This procedure guarantees that everyone has the same idea of what success is. Guesswork is eliminated by applying structured techniques like QFD, utilizing formal documents, and separating engineering specifications from customer needs. This saves time, avoids costly errors, and ensures that the finished product lives up to expectations.