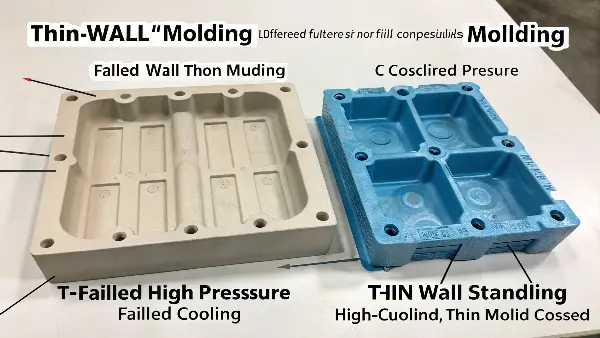

Having to design lighter parts, faster to produce, with less material, yet feeling that thin-wall injection molding is the answer, only to apply conventional design rules and receive short shots, warpage, and failures. You feel jammed-in, unable to push the boundaries without expensive mold rework and project delays. It is a no-good position to be in.

Mastering thin-wall design requires a systems approach, not just part design. Success requires choosing high-flow materials like specific grades of PP, PE, or ABS, and designing the part with uniform wall thickness and gentle transitions. Your mold must feature robust cooling, excellent venting, and often multiple gates. And finally, the injection process itself must be extremely fast and high-pressure if it is to fill the cavity before the plastic freezes. It’s a complete package where the part, mold, and machine must work in perfect harmony.

This sounds like a lot to juggle, and it is. I remember the first time I worked on a thin-wall container project. We followed all the "rules" we knew, but the results were a disaster. It taught me that thin-wall molding isn’t just an extension of standard molding; it’s a completely different discipline. It demands a new way of thinking. Let’s walk through this new mindset together, breaking down each critical component so you can tackle these projects with confidence.

What Makes Thin-Wall Molding So Different From Standard Molding?

You have followed all the customary design guidelines for ribs, bosses and drafts, yet your thin-wall parts refuse to fill. It can be infuriating when proven methods simply don’t work. The plastic seems to freeze the instant it enters the mold. You see massive pressure drops across the part, and try as you might, you cannot get it to fill completely, no matter how you adjust the process. It’s a frustrating roadblock for many experienced designers.

The big difference is L/t ratio, or the ratio of the plastic’s flow length to the wall thickness. In thin-wall molding, this ratio is very high, meaning the plastic cools and solidifies almost instantly as it touches the cold mold walls. This forces you to have extremely high injection speeds and pressures just to fill the part. This quick cooling also locks in massive amounts of internal stress, making material choice, gate location, and venting strategies absolutely key to success.**

Let’s dive deeper into what makes this process so unique. It’s not just about making things thinner; it’s about managing physics under extreme conditions. I learned early on that you have to respect the plastic’s behavior at these speeds and pressures. It doesn’t forgive small mistakes in the design of the part or the mold. Understanding these core differences is the first step toward mastering the technique and avoiding costly trial and error.

The Race Against Solidification

In conventional molding, you have a pretty generous processing window. The plastic flows into a thicker cavity, so the outer layers solidify while the core remains molten and allows the flow front to continue advancing. In thin-wall molding-with thicknesses often below 1mm-there is no molten core. The entire cross-section of the flow wants to freeze instantly. That is why the L/t ratio becomes the governing factor. A conventional part might have an L/t ratio of 100:1. A thin-wall part can easily exceed 200:1 or even 300:1. That means the plastic has to travel an incredibly long distance relative to its thickness before it freezes solid.

Pressure, Speed, and Machine Power

To win this race against solidification, you need brute force. This means much higher injection speeds and pressures than in conventional molding.

- Injection Speed: You must fill the cavity in a fraction of a second, often less than 0.5 seconds. This minimizes the time the plastic has to cool and freeze.

- Injection Pressure: Packing the part requires enormous pressure to overcome the resistance of the rapidly cooling plastic. This often requires machines capable of delivering 25,000 to 30,000 PSI, sometimes more.

This is why you can’t just use any molding machine. You need a high-performance machine, often an electric or hybrid model, built for speed, pressure, and precision. A standard hydraulic press usually can’t provide the acceleration and responsiveness required.

Warpage and Stress on a New Level

Because the plastic is injected so quickly and freezes under such high pressure, a huge amount of stress is locked into the part. This makes thin-wall parts highly susceptible to warpage.

- Differential Shrinkage: Even tiny temperature variations across the mold surface can cause significant differences in shrinkage, pulling the part out of shape.

- Material Orientation: The high-speed flow strongly aligns the polymer chains and any fillers (like glass fibers) in the direction of flow. This creates anisotropic shrinkage, meaning the part shrinks differently in the flow direction versus the cross-flow direction, which is a primary driver of warpage.

Here’s a simple breakdown:

| Feature | Standard Injection Molding | Thin-Wall Injection Molding |

|---|---|---|

| Wall Thickness | Typically > 2.0 mm | Typically < 1.5 mm, often < 1.0 mm |

| L/t Ratio | < 150:1 | > 200:1 |

| Injection Speed | Moderate | Extremely Fast (< 0.5s fill time) |

| Injection Pressure | 10,000 – 20,000 PSI | 25,000 – 40,000+ PSI |

| Primary Challenge | Sink marks, voids | Short shots, warping, high stress |

| Machine Requirement | Standard Hydraulic/Electric | High-Speed Electric/Hybrid |

| Mold Venting | Important | Absolutely Critical |

Understanding these fundamental differences is key. You’re not just designing a thin part; you’re designing a high-speed, high-pressure manufacturing system.

How Do You Select the Right Material for a Thin-Wall Application?

You’d selected a standard material that works just fine for your company’s other products, but it simply won’t fill your new thin-wall design. The material data sheet looked just fine, but now you’re fighting consistent short shots and project delays. You are starting to realize that the wrong resin can bring a promising project to a grinding halt. The pressure is on to find a solution quickly.

Of the material properties, MFI or MFR has the highest importance for thin-wall applications. You need to select resins that are engineered for easy flow. This will give the plastic the ability to fill a thin cavity before freezing. Base resins that are commonly used include high-flow PP, PE, and special grades of ABS or PC/ABS. After MFI, material modulus or stiffness should be considered to provide the part with some structural integrity even with its thin wall.

Let’s break down the material selection process. It’s more than just looking at a number on a data sheet. I once had a client who insisted on using their standard-grade ABS for a new electronics enclosure that was only 0.8mm thick. No matter what we did on the machine, we couldn’t fill the part. We switched to a high-flow PC/ABS blend, and it ran perfectly on the third shot. That experience taught me that the material isn’t just a choice; it’s the foundation of the entire project.

It All Starts with Melt Flow

The Melt Flow Index (MFI) or Melt Flow Rate (MFR) is your primary guide. This value tells you how easily a melted plastic flows under a specific temperature and pressure. A higher number means lower viscosity and better flowability.

- Standard Materials: Might have an MFI in the range of 5-15 g/10 min.

- Thin-Wall Materials: You should be looking for materials with an MFI of 30, 40, 50 g/10 min, or even higher.

Material suppliers formulate these high-flow grades specifically for thin-wall applications by controlling the polymer chain lengths. Shorter chains flow more easily, resulting in a higher MFI. Always tell your material supplier that your application is for thin-wall molding; they will guide you to the correct grades.

Balancing Flow with Performance

While high flow is essential, you can’t sacrifice the mechanical properties required for your product’s function. This is where the balancing act comes in.

- Stiffness (Flexural Modulus): A part with thin walls can be flimsy. You need a material with enough stiffness to prevent the part from feeling cheap or failing under normal use. Sometimes, this means choosing a glass-filled material, but be aware that fillers can hinder flow and increase warpage.

- Impact Strength (Izod): Thin parts are more susceptible to cracking. The material must have good impact resistance, especially if it’s a consumer product that might be dropped.

- Heat Deflection Temperature (HDT): If the part will be exposed to heat, you need to ensure the material won’t deform.

Here is a look at some common material choices and their characteristics for thin-wall molding:

| Material Type | Typical MFI Range (g/10 min) | Strengths | Weaknesses | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polypropylene (PP) | 30 – 100+ | Excellent flow, good chemical resistance, low cost | Low stiffness, can feel flimsy | Food containers, caps, medical devices |

| Polyethylene (HDPE) | 20 – 50 | Good flow, tough, low cost | Lower heat resistance than PP | Lids, single-use packaging |

| ABS | 20 – 60 | Good stiffness and impact balance, good aesthetics | Higher viscosity than olefins | Electronic housings, device covers |

| PC/ABS Blends | 20 – 40 | Excellent impact strength, good heat resistance | More expensive, can be harder to process | Laptop cases, mobile phone bodies |

| Polystyrene (HIPS) | 15 – 30 | Good stiffness, excellent detail replication | Brittle, poor chemical resistance | Yogurt cups, disposable cutlery |

When you discuss a project with a material supplier, come prepared with your target wall thickness, flow length, and critical performance requirements (like impact strength or operating temperature). This information will allow them to recommend the best possible material that balances processability with end-use performance.

How Must Your Part Design Change for Thin-Wall Molding?

You’ve designed a beautiful, functional part, but your mould-flow analysis shows it won’t fill. The results are a sea of red, indicating high pressures and frozen flow fronts. You followed good design practices, but they weren’t enough for the thin walls you needed. Now you have to go back and change the design, but you’re not sure which changes will actually solve the problem. This is a common point of failure where Industrial Design clashes with manufacturing reality.

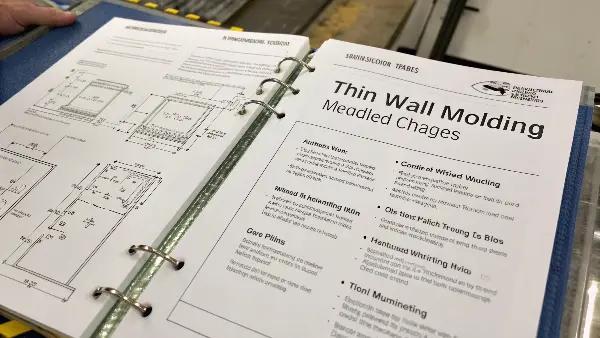

For thin-wall parts, the most important thing is flow. Keeping the wall perfectly uniform wherever possible is the single most important rule of designing for thin-wall parts. Avoid sharp corners and use gentle sweeping radii instead. Also, design ribs to be no more than 50-60% of the thickness of the wall to prevent sink and promote flow. Plan your gate locations in the initial design by giving the plastic the shortest most unobstructed path to fill the extremities of the part.

You need to rethink your design approach from the ground up: you need to stop thinking about a static part and start thinking about how a jet of molten plastic will behave inside the cavity. I once worked on a medical device housing that featured a number of sharp internal corners. We could not get the part to fill past those corners without flashing the mold elsewhere. We went back in, added a 0.5mm radius to every corner, and the part filled perfectly. It was a simple change that made all the difference because it respected the physics of high-speed flow.

The Golden Rule: Uniform Wall Thickness

In thin-wall molding, any change in wall thickness acts as a flow restriction or a hesitation point. If the plastic has to flow from a thin section into a slightly thicker one, it will slow down, lose pressure, and potentially freeze. If it flows from thick to thin, it will accelerate, which can cause jetting and other defects.

- Ideal Scenario: Keep the wall thickness constant across the entire part.

- If You Must Change: Make the transition as gradual and smooth as possible. Think of it like designing a smooth highway for the plastic, not a road with sharp turns and potholes.

This is the most critical rule, and violating it is the most common cause of failure.

Ribs and Bosses: A Delicate Balance

Ribs and other features are necessary for strength, but they are also interruptions to flow.

- Rib Thickness: Stick to a rib thickness of 50-60% of the nominal wall. Any thicker, and you risk prominent sink marks on the opposite surface. Any thinner, and they may not fill at all.

- Rib Height: Keep ribs shorter than 3 times the nominal wall thickness if possible. Tall, thin ribs are extremely difficult to fill and cool.

- Draft: Apply as much draft as you can to ribs and bosses (1 to 2 degrees per side is great) to help with ejection, as the high packing pressures can make parts stick.

- Coring: Core out thick sections and bosses to maintain that crucial uniform wall thickness.

Gate Location Strategy

You cannot treat gating as an afterthought. It must be part of the initial product design discussion.

- Gate on the Thickest Section: Always gate into the thickest possible area of the part to establish a wide, stable flow front.

- Centralized Gating: A single hot tip gate in the center of a round part is ideal. It promotes radial flow, which helps balance the filling pattern and minimize warpage.

- Multi-Point Gating: For long or complex parts, you will likely need multiple gates or a fan gate. Work with your mold maker and use mold-flow simulation to determine the optimal number and position of gates to ensure the entire cavity fills at the same time. This avoids weld lines in critical areas and reduces overall injection pressure.

Here’s a design checklist to review before you finalize your CAD model:

| Design Element | Conventional Part | Thin-Wall Part | Why it Matters for Thin-Wall |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wall Thickness | Maintain +/- 25% | Strive for 100% uniformity | Prevents hesitation and pressure drops. |

| Corners/Radii | 0.5x wall thickness is good | > 1.0x wall thickness is better | Smooth, generous radii maintain flow velocity and reduce stress. |

| Ribs | 60-70% of wall thickness | 50-60% of wall thickness | Avoids sink marks and ensures ribs will fill without stealing flow. |

| Gate Consideration | Done during mold design | Part of initial product design | Gate location dictates the entire filling dynamic and part quality. |

| Tolerance | Standard tolerances | Tighter tolerances required | Because the part is thin, even small variations can affect fit and function. |

Thinking like a fluid dynamics engineer, not just a product designer, is the key to creating successful thin-wall parts.

How Do Rheology and Shear Heating Control Thin-Wall Fill Success?

When we go below about 1 mm wall thickness, the behavior of molten plastic changes from “forgiving” to unforgiving. Viscosity is no longer just a property listed on a data sheet; it’s a variable that shifts every millisecond as shear rate increases. Extreme injection speeds cause high shear thinning, temporarily reducing viscosity and allowing the melt to sprint through thin flow channels before freeze-off. Extreme shear can also cause viscous heating, locally increasing melt temperature and disrupting flow balance.

Therein lies the challenge with thin-wall molding: the processing window is tiny. Go too slow and the melt freezes up before it fills the cavity. Go too fast and you risk material degradation, burning, jetting and flow instability. Expert thin-wall mold designers learn to finely balance melt temp, mold temp, and injection acceleration to keep the plastic moving just long enough to fill the cavity, but no longer.

Why Gate Type Is Just as Important as Gate Location

Gate Location Gets All the Attention – But Gate Type is Equally Important

Engineers tend to obsess over gate location, but with thin-wall you also need to choose the right gate type to avoid failure.

Fan gates and film gates are ideal for thin-wall because they open up into a wide, thin front. This means less shear stress and pressure drop as the plastic enters the cavity. Valve gates for hot runner systems provide extremely fast, clean opening with pinpoint accuracy on opening timing, allowing you to fill cavities in fractions of a second. Small edge gates or pin gates severely restrict flow, causing localized freeze-off and very high shear that will burn and gouge the cavity.

Gate thickness, land length and transition radius all affect how smoothly the melt can transition into accelerated flow in the cavity. When designing thin-wall molds, the gate isn’t just a point of entry – it’s a flow-conditioning tool that must properly shape velocity, shear, and temperature gradients from the very first millimeter of cavity flow.

Molecular and Fiber Orientation Drive Warpage in Thin Walls

Thin-Walled Parts warp… Because molecules and fibers like to line up during flow

One of the reasons parts warp after cooling is because polymers and fill fibers have a tendency to orient along the flow direction. When filled with fibers, thin-wall injection molding forces the fibers to align in flow direction, leaving you with a highly anisotropic part.

Since the part exhibits different stiffness in the flow direction than across it, the material will shrink more in one direction than the other. Warpage occurs when cooling (and therefore shrinkage) is uneven across the part.

To control fiber orientation, you must carefully balance flow through gate number, gate location, and sometimes flow rotation. Using multi-gate designs lets you compensate for orientation by having two flow fronts pulling in opposite directions, minimizing overall shrinkage mismatch.

How Does Mold Design Adapt for Thin-Wall Molding?

You have the perfect part design and the appropriate high-flow material, but the molder is struggling. They complain about flash, burnt parts, and sticking. They have to slow the cycle time way down just to make an acceptable part, defeating the purpose of thin-wall molding. You suspect the mold itself is the problem, but you are not sure what to ask the mold maker to change.

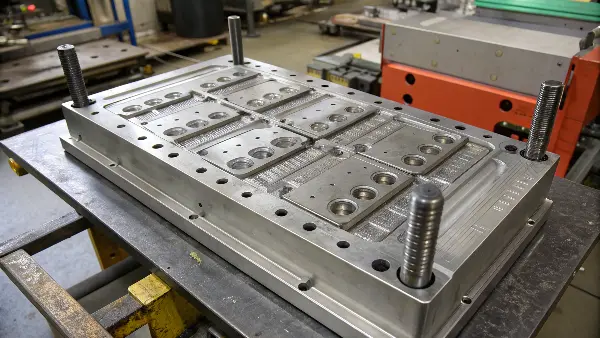

**A thin-wall mold is a high-performance machine. It must be built from high-hardness steels like H-13 or S-7 to withstand extreme injection pressures without flexing. The cooling system must be extensive and strategically placed to remove heat rapidly and uniformly. Most importantly, venting must be deep, wide, and cover at least 30% of the part’s perimeter to allow trapped air to escape almost instantly. Without these three elements—strong steel, aggressive cooling, and massive venting—the mold will fail.

Your mold is not just a cavity; it’s the most critical piece of equipment in the entire process. I learned this the hard way on a project for a disposable cup. The mold was built by a shop that didn’t specialize in thin-wall tooling. It flexed under pressure, the cooling was uneven, and it was constantly flashing. We spent weeks trying to fix it before finally commissioning a new, purpose-built mold. The second mold ran perfectly from day one, proving that the investment in proper tool design and construction pays for itself almost immediately.

A Foundation of Steel

Standard molds are often made from P20 steel. This is not sufficient for thin-wall applications.

- High Pressures: The injection pressures can exceed 30,000 PSI. This force will physically bend a mold made from softer steel, causing the parting line to open up and create flash.

- Mold Deflection: Even a tiny amount of deflection (0.001" or 0.025mm) can ruin a thin-wall part.

- Solution: You need high-hardness, pre-hardened, or through-hardened tool steels. H-13, S-7, and other similar grades provide the rigidity needed to contain the immense pressures without flexing. Robust support pillars and thick mold plates are also essential.

Cooling is King

The goal of thin-wall molding is speed. You want the shortest possible cycle time, and that is almost always limited by cooling.

- Rapid Heat Removal: You are injecting hot plastic very quickly, so you must remove that heat just as quickly. If you don’t, the cycle time will extend, and you lose the primary economic advantage.

- Uniformity is Key: Cooling must be perfectly uniform across the entire part. Any hot spots will cause differential shrinkage, leading to severe warpage.

- Design Strategy: This means designing the mold with as many cooling channels as possible, placed as close to the molding surface as is safe. Use techniques like conformal cooling, baffles, and bubblers to get water into difficult-to-reach areas like cores and ribs. I often specify separate cooling circuits for the core and cavity so I can fine-tune the temperatures independently to control warpage.

Venting: Let the Air Out

When you inject plastic into a mold at high speed, you are compressing the air that’s already in the cavity. If that air has no way to escape, it will get trapped.

- Trapped Air: This compressed air becomes superheated, which can burn the plastic, causing black or brown streaks. It can also create a pocket of resistance that prevents the part from filling completely, resulting in a short shot.

- The Solution is Massive Venting: In thin-wall molding, you can’t have too much venting. Vents need to be placed at the end of every flow path and along the entire parting line.

- Vent Depth: Typically 0.0005" to 0.001" (0.012mm to 0.025mm), depending on the material. This is deep enough for air to escape but too shallow for the plastic to flash.

- Vent Land: Keep the land area short (around 0.04" or 1mm) before opening up to a much deeper channel to let the air escape the mold completely.

I often recommend that at least 30-40% of the part’s perimeter be vented. In some extreme cases, we even put venting pins in areas prone to gas traps. It’s a critical, non-negotiable part of the design.

Thin Wall Design: Clamp Force, Mold Deflection and “Breathing” Under Ultra-High Pressure

Thin-wall parts demand very high cavity pressures due to aggressive cooling and high L/t ratios. These pressures translate into significant mechanical forces bearing down on the mold. Insufficient clamp tonnage or mold plate stiffness can cause the tool to deform elastically while injection is happening. Opening of the parting line at a microscopic scale (“mold breathing”) is a direct cause of flash and lack of dimensional control.

Therefore, clamp force should be calculated based on projected area times peak cavity pressure, plus a margin for pressure spikes. Tooling should be designed with thick plates, dense support pillars, and high modulus mold steel to prevent elastic deflection. Rigidity is half the battle in thin-wall molding.

Engineering Cooling Channels for Maximum Heat Flux

Cooling design is not just how many channels you can cram into a thin-wall mold; it’s about how high of a heat flux you can generate. Since cooling must extract enough heat to maintain short cycle times, the distance from cooling channel to cavity surface should be no greater than twice the wall thickness, typically.

Cooling flow should also be turbulent to maximize heat transfer coefficients. Channel diameter and flow velocity must be sized properly to induce turbulence. Core and cavity should have separate, independently-controlled cooling loops to fine tune temperature gradients across the part for warpage control of highly oriented thin parts. Conformal cooling lets you put cooling right where the heat is instead of where it’s convenient to drill.

Injection Unit Dynamics: Acceleration is Better Than Top Speed

We talk a lot about pressure rises in thin-wall molding, but rapid acceleration of the screw is just as important. Remember that the cavity must fill before a frozen skin forms and halts flow. That means, ideally, the machine goes from zero to top speed in zero time.

Only electric and hybrid machines have servo drives that are capable of pushing that level of acceleration smoothly and consistently. Hydraulics, even with large accumulators for high peak pressures, can be too sluggish to respond quickly enough for thin-wall molding. This is why machine choice is an integral part of thin-wall system design, versus simply “capacity shopping.

Conclusion

Mastering thin-wall injection molding is a journey beyond standard textbook rules. It requires you to adopt a holistic system where the part design, a high-flow material, a robust mold, and a high-speed process all work together. By focusing on flow and maintaining uniform walls, you’ll be able to push the envelope with lighter, faster, and more economical parts by investing in high-performance tooling that cools and vents well.