Developing a new plastic part is exciting, but choosing the wrong prototyping method can waste thousands of dollars and weeks of your time. This mistake can set back your entire project, delay your launch, and let competitors get ahead. A strategic prototyping plan, however, allows you to pick the right method for each stage, from concept to production, ensuring you invest your resources wisely and stay on schedule.

Creating a strategic prototyping plan for plastic parts involves matching the prototype’s fidelity and function to your development stage. Early on, use low-cost methods like 3D printing for form and fit checks. As you refine the design, move to higher-fidelity options like CNC machining for functional testing. Finally, use methods like rapid tooling for pre-production validation. This phased approach ensures you gather the right feedback at each step without overspending, leading to a successful final product.

Over my years in the mold industry, I’ve seen many clients struggle with prototyping. They either spend too much, too early, or they create a prototype that doesn’t answer their key questions. This often leads to frustration and costly redesigns down the line. A clear strategy isn’t just a nice-to-have; it’s essential for a smooth and successful product launch. It provides a roadmap that guides your decisions, turns your idea into a tangible product, and saves you from preventable headaches. Let’s break down this process so you can build your own effective plan.

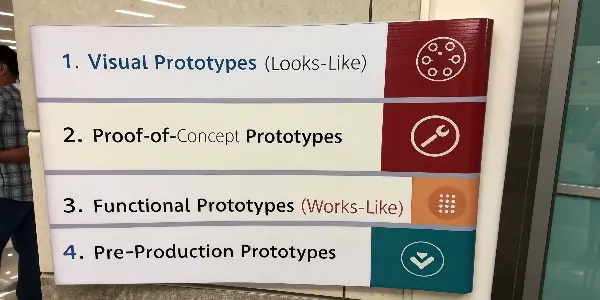

What are the four types of prototyping?

You know you need a prototype, but the options seem overwhelming. Low-fidelity, high-fidelity, functional, visual… what do they all mean? Choosing the wrong type means you might test for function with a model that can only show aesthetics, or spend a fortune on a detailed model when a simple one would have done the job. Understanding the four main types of prototypes clarifies their purpose, helping you select the perfect one for your current needs.

The four main types of prototypes are categorized by their purpose and fidelity. They are: 1. Visual Prototypes (Looks-like), which focus on aesthetics and form. 2. Proof-of-Concept Prototypes, which test a single, core function. 3. Functional Prototypes (Works-like), which mimic the final product’s functionality but not necessarily its appearance. 4. Pre-production Prototypes, which are nearly identical to the final product and are used for final testing and validation before mass production.

Thinking about these four types as stages in a journey can be really helpful. Each one answers a different set of questions that you’ll have as your product idea develops. It’s about getting the right information at the right time without overcomplicating things. Let’s look at when and why you would use each one.

Matching Prototypes to Your Goals

Your prototype’s job is to give you answers. If you’re asking, "What will this look like on a shelf?" you don’t need a model that performs complex functions. Similarly, if you need to know, "Will this gear mechanism withstand 1,000 cycles?" a simple visual model won’t help. The key is aligning the prototype type with your current development goal.

A Deeper Look at Each Type

Let’s break down the purpose of each prototype type. This will help you see how they build on one another, guiding your project from a simple idea to a market-ready product.

| Prototype Type | Primary Question Answered | Common Use Case | Common Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visual (Looks-like) | "What will it look like and feel like?" | Marketing photos, focus groups, ergonomic checks. | SLA 3D Printing, Clay/Foam models |

| Proof-of-Concept | "Is the core idea technically feasible?" | Testing a novel mechanism or electronic circuit. | Breadboards, FDM 3D Printing |

| Functional (Works-like) | "Does it work as intended?" | Field testing, performance validation, stress tests. | CNC Machining, SLS 3D Printing |

| Pre-production | "Is this ready for mass production?" | Final design validation, mold testing, assembly checks. | Rapid Tooling, Pilot Production |

When I first started my company, we were developing a new casing for an electronic device. We began with a simple 3D-printed visual model. Holding it helped us realize the edges were too sharp. After fixing the design, we moved to a CNC-machined functional prototype to test snap-fits and durability. This step-by-step process, using the right type of prototype at each stage, saved us from a costly mold rework later.

How to create a plastic prototype?

So, you have an idea and know which type of prototype you need first. But what’s the actual process of turning that digital file into a physical object you can hold? The path from concept to creation can seem complex, with different technologies and materials to consider. If you miss a step or choose the wrong production method, you could end up with a prototype that doesn’t accurately represent your design, wasting both time and money.

To create a plastic prototype, you first need a 3D CAD (Computer-Aided Design) model of your part. Next, select the best prototyping method based on your needs—common options include 3D printing (for speed and form), CNC machining (for precision and strength), or rapid tooling (for small production runs). After selecting the method, choose a material that matches your test requirements. Finally, send the files to a manufacturing partner who will produce the physical prototype for your evaluation.

The journey from a digital dream to a physical part is one of the most exciting parts of product development. I remember the first time I held a part I had designed myself; it was a game-changer. This process is where your idea starts to feel real. The method you choose will heavily influence the quality, cost, and speed of your prototyping stage. Making an informed choice here is critical, so let’s get into the details of the most common methods for plastic parts.

Choosing Your Prototyping Path

The two most dominant technologies for creating plastic prototypes are 3D printing and CNC machining. They are fundamentally different in how they create a part, and that difference has a huge impact on the final result.

-

3D Printing (Additive Manufacturing): This method builds the part layer by layer from a digital file. It’s like building a sculpture with a high-tech hot glue gun. Because it adds material instead of removing it, it can create incredibly complex internal geometries that would be impossible with other methods. It’s generally faster and often cheaper for one-off, complex parts.

-

CNC Machining (Subtractive Manufacturing): This method starts with a solid block of plastic and uses computer-controlled cutting tools to carve away material until only the final part remains. It’s incredibly precise and can produce parts with excellent surface finishes and tight tolerances. The prototypes are also made from the same material as the final injection-molded part, so their mechanical properties are very representative.

Comparing the Core Methods

Deciding between 3D printing and CNC machining comes down to what you need to test. Are you checking the look and feel, or are you testing if the part can withstand mechanical stress?

| Feature | 3D Printing (e.g., SLA, FDM, SLS) | CNC Machining |

|---|---|---|

| Process | Additive (builds layer by layer) | Subtractive (carves from a block) |

| Speed | Very fast for single or few parts | Slower setup, but fast for duplicates |

| Complexity | Excellent for complex internal features | Limited by tool access |

| Material Properties | Good, but can be weaker due to layers | Excellent, same as production-grade plastic |

| Best For | Early-stage visual models, form/fit tests | Functional prototypes, high-precision parts |

I once worked with a client, Michael, who needed to test a snap-fit clip. He initially chose 3D printing for speed. The prototype looked great, but the clip broke after just a few uses because the layered structure of the 3D print created a weak point. We then made the same part using CNC machining from a block of ABS plastic. That prototype performed perfectly, just like the final molded part would. This experience taught us a valuable lesson: for functional testing of mechanical features, CNC machining is often the more reliable choice.

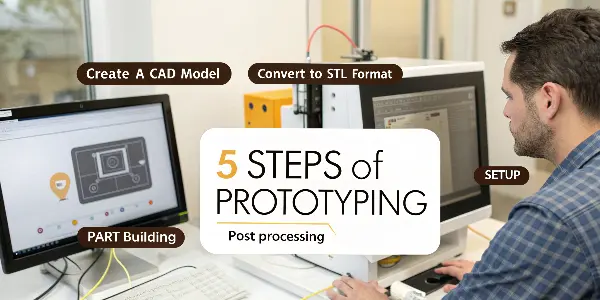

What are the 5 steps of rapid prototyping?

Rapid prototyping sounds great—it’s fast, efficient, and lets you test ideas quickly. But what does the process actually look like from start to finish? Without a clear roadmap, you might get lost in technical details or miss a crucial validation step. This can turn a "rapid" process into a slow and frustrating one. Knowing the specific steps helps you stay organized and get the most value out of the technology, ensuring your project keeps moving forward smoothly.

The 5 essential steps of rapid prototyping are: 1. Create a CAD Model, which is the digital blueprint of your design. 2. Convert to STL Format, a standard file type that slices the model for the machine. 3. Machine Setup, where the operator prepares the machine and material. 4. Part Building, the automated process where the machine creates the physical part. 5. Post-Processing, which involves cleaning, curing, or finishing the part to prepare it for evaluation and testing.

These five steps form the backbone of modern product development. Gone are the days of waiting weeks for a single prototype. With rapid prototyping, especially 3D printing, I’ve seen teams go from an idea in the morning to a physical part in their hands by the end of the day. This speed allows for incredible agility. You can test, fail, learn, and iterate faster than ever before. Understanding this workflow is key to leveraging its full potential. Let’s walk through what happens at each stage.

From Digital to Physical

The rapid prototyping workflow is a systematic process designed for speed and accuracy. Each step builds on the last, and paying attention to detail at every stage is crucial for a successful outcome.

Step 1: Create a CAD Model

Everything starts with a high-quality 3D CAD model. This is the master blueprint. Software like SolidWorks, Fusion 360, or CATIA is used to design the part with precise dimensions. At this stage, it’s vital to think about the final manufacturing process. For instance, if you plan for injection molding later, you should design features like draft angles into your prototype model. This foresight saves you from major redesigns later.

Step 2: Convert to STL and Prepare for Building

Once the CAD model is complete, it’s exported as an STL (stereolithography) file. This file format describes the surface geometry of the 3D model using a mesh of triangles. This STL file is then imported into "slicer" software, which digitally cuts the model into hundreds or thousands of thin horizontal layers. The slicer software also generates the toolpaths and instructions the machine will follow to build each layer. The operator will set key parameters here, like layer height and support structure placement.

Step 3, 4, & 5: Setup, Build, and Post-Process

The final steps are mostly hands-on. The machine operator loads the prepared file, selects the material, and calibrates the machine. The build process is typically automated, with the machine meticulously creating the part layer by layer. After the build is complete, the part must be removed and post-processed. This can involve removing support structures from a 3D print, curing it under UV light (for SLA), or removing excess powder (for SLS). A quick sanding or polishing can also be done to improve the surface finish before it’s ready for testing. Each of these steps is critical for a high-quality result.

What is the most important element of prototyping?

With all the talk about methods, materials, and steps, it’s easy to get lost in the technical details. You could have the most advanced 3D printer and the best materials, but still end up with a useless prototype. Why? Because you might be focusing on the wrong thing. Without a clear purpose, your prototype is just a piece of plastic. It won’t give you the answers you need to move your project forward, leading to wasted effort and a stalled development cycle.

The most important element of prototyping is having a clear objective. You must define exactly what you want to learn from the prototype before you make it. Are you testing ergonomics, validating a mechanism’s function, or checking for assembly issues? Each prototype should be an experiment designed to answer a specific question. This focused approach ensures that every prototype you create provides valuable feedback, minimizes waste, and moves your product one step closer to successful production.

I learned this lesson the hard way. Early in my career, I was so excited by the technology that I would just print a design to "see how it looked." Sometimes it was helpful, but often it was a waste of a day. It wasn’t until I started working with experienced engineers like Michael that I understood the power of purpose-driven prototyping. They never just "made a prototype." They would say, "Let’s build this model to test the "living hinge" durability," or "We need a prototype to confirm clearance with the PCB." This mindset shift was transformative.

Start with the "Why"

Prototyping isn’t about making a perfect replica of your final product on the first try. It’s an information-gathering tool. The quality of the information you get is directly related to the quality of the questions you ask.

Define Your Test Plan

Before you even send a file to be made, sit down and write down your goals.

- Primary Question: What is the single most important question this prototype needs to answer? (e.g., "Does this snap-fit hold with 5 lbs of force?")

- Secondary Questions: What other, less critical things can we learn? (e.g., "What is the texture like? Does it feel too heavy?")

- Success Criteria: How will you measure the results? What defines a pass or a fail? (e.g., "The snap-fit must survive 50 cycles without breaking.").

An Example of a Focused Objective

Let’s say you are designing a new battery cover for a remote control. Instead of just making a general prototype, your objective could be:

- Objective: To validate the fit and function of the new latching mechanism and confirm easy battery replacement for the user.

- Method: CNC machine the cover from ABS plastic to accurately simulate the strength and flexibility of the final part.

- Test Plan:

- Assemble the prototype cover onto the main housing. Does it fit without gaps?

- Cycle the latch 100 times. Does it show signs of wear or failure?

- Ask five different users to open the cover, replace the batteries, and close it. Observe for any difficulties.

By defining your goal so clearly, you guarantee that the prototype will provide actionable feedback. You’re no longer just making an object; you’re conducting an experiment. This focused approach is the true secret to effective and strategic prototyping.

Conclusion

Creating a successful plastic part relies on a smart prototyping strategy. It’s not about finding one perfect method, but about choosing the right tool for each stage of development. By starting with visual models, moving to functional tests, and finishing with pre-production samples, you systematically eliminate risks. This purposeful, step-by-step approach saves you from costly errors, speeds up your timeline, and is the surest path to getting your product right.