Injection molding is a very critical process involving mold venting. It is used to make sure that the gases that are trapped in the mold are released. Defects such as burn marks and voids may develop without proper venting. Ventilation systems also play a crucial role in ensuring the quality of indoor air in manufacturing environment. They assist in the regulation of emissions and provision of safe working environment. Adequate ventilation leads to quality products and safety of the workers.

The science of venting of molds is a science of balancing the material and the flow of air. This balance plays a critical role in minimizing the batch of defects and maximizing concurrence in production. High-tech systems and inventions are on-going to enhance venting of molds.

In this paper we examine the science of venting of molds. We talk of the behavior of gases in injection molding and its impact. Ventilation systems, which are effective in manufacturing, are also pointed out.

Understanding this process is one of those "aha!" moments I’ve seen many clients experience. It shifts the focus from just the plastic and the machine to the mold itself as a sophisticated tool. Proper venting isn’t a minor detail; it’s a core principle of good mold design. It ensures the plastic can fill the cavity completely and form a solid, uniform part without fighting against a pocket of compressed air. Let’s dig into why this happens and how to get it right.

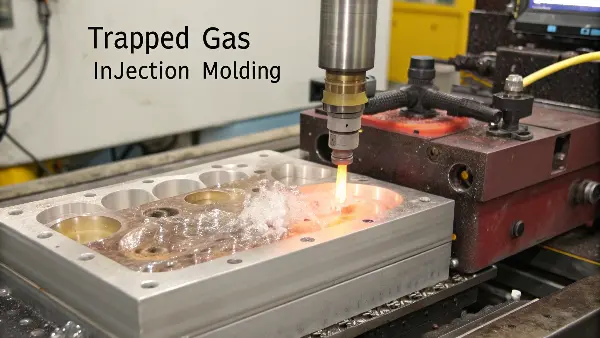

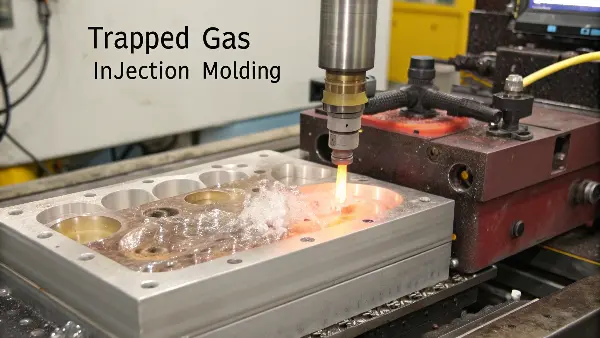

What Exactly Is Trapped Gas and Why Does It Ruin Your Parts?

Are mysterious defects continuing to stump you, despite going through all your normal troubleshooting steps? You change your injection parameters, you dry your material to perfection, and the defects persist. It’s very frustrating when you cannot find what is causing this, as time is being wasted along with parts being scrapped. In reality, invisible forces inside your mold are often the cause: trapped gas. It silently destroys your parts, but since you cannot see it, it is almost always the last thing looked at.

Trapped gas is the air and volatile compounds that fail to escape the mold cavity as it’s being filled with molten plastic. This gas becomes cornered and compressed, causing extreme pressure and temperature spikes in localized hotspots. This "diesel effect" burns the plastic, creating black or brown marks. It also creates back pressure that prevents the mold from filling completely – a condition known as short shots – and also results in weak and visible weld lines where plastic fronts meet but fail to fuse properly, creating a structurally compromised part.

To really get to the bottom of this, we need to think about the physics at play. Imagine pushing a plunger into a syringe with your finger over the end. You can only push it so far before the compressed air inside pushes back. Now, imagine that plunger is molten plastic moving at incredible speed, and the trapped air has nowhere to go. The pressure builds up instantly. The temperature of that trapped gas can skyrocket to levels far higher than the plastic’s melt temperature. This is where the real damage begins.

How Does Trapped Gas Cause Defects?

The root of the problem is that gas is compressible, but the molten plastic isn’t. When the plastic flow front traps a pocket of air, it squeezes it into a smaller and smaller space. This rapid compression generates immense heat, often leading to a few key problems:

- Burn Marks (Dieseling): The gas heats up so much it scorches the plastic, leaving black or dark brown residue on the part. This is a telltale sign of a venting issue.

- Incomplete Fill (Short Shots): The back pressure from the trapped gas can be strong enough to physically stop the plastic from filling the furthest points of the cavity.

- Weld Line Weakness: Where two plastic flow fronts meet, they are supposed to fuse. But if a pocket of trapped gas is sitting at that meeting point, it prevents a clean, strong bond from forming.

Why Isn’t This Always Obvious?

The signs aren’t always as clear as a large black scorch mark. Sometimes, poor venting manifests in more subtle ways, which can be even more frustrating for business owners like Michael who rely on consistent quality.

| Subtle Sign | What It Looks Like | Why Venting is the Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Surface Finish | Dull patches or flow marks in areas far from the gate. | Trapped gas disrupts the plastic’s contact with the mold surface, preventing it from perfectly replicating the polished steel. |

| Warpage | The part distorts or bows after ejection from the mold. | Inconsistent filling pressure caused by trapped gas can create internal stresses that are released once the part cools. |

| Inconsistent Part Weight | Parts from the same run have slightly different weights. | This indicates that some cavities are not filling as completely as others, often due to variations in how effectively gas is escaping. |

I once worked with a client who was struggling with a high-gloss part that had persistent dull spots. They blamed the material, the polish, everything but the vents. We took the mold, added a few strategically placed vents in the problem area, and the issue vanished. It was a simple fix, but it required understanding that gas behavior was the true culprit.

The Role of Gas Behavior in Mold Cavities

Gas behavior inside a mold cavity significantly influences injection molding quality. Gases are able to expand and contract with their temperature and pressure inside the mold, which needs careful management to maintain the integrity of molded parts.

The behaviour of the gases directly influences the surface and structural properties of the final product. An excess build-up of gases leads to surface blemishes. Such blemishes include burn marks or voids that are harmful to both product aesthetics and strength.

To handle gas behavior effectively, manufacturers should consider:

- Accurate control of temperature and pressure settings

- Application of advanced software for simulation to predict gas dynamics

- Regular monitoring of mold conditions during production

Understanding how gases behave under various conditions helps prevent defects. This awareness is very important for ensuring high-quality production outcomes. Properly managing gas behavior in molds leads to smoother operations and improved product consistency.

Where Does All This Gas Come From in the First Place?

You know that the trapped gas is your nemesis, but you may wonder where it comes from. If you begin with a clean, empty mold and simply cast a part into it, where does all this aggravating gas come from? The natural assumption might be that the mold is merely empty space, but the fact of the matter is that it’s filled with air, and that’s not all. Locating the sources is the first step in controlling them.

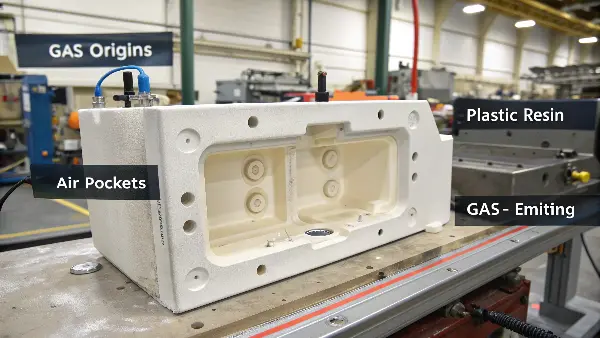

The gas inside a mold cavity comes mainly from two sources. First is the atmospheric air that fills the cavity before injection begins, which needs to be pushed out. Second, and more problematic often, are the volatile gases released by the plastic resin itself while it gets heated to its melting temperature. These might include moisture, binders, flame retardants, and other additives, which turn into gas under conditions of heat and pressure and add to the total volume that needs to be vented.

Thinking about both sources is critical for effective mold design and process control. You can’t eliminate the air in the cavity, so you must design a way for it to escape. But you can take steps to minimize the gas generated by the plastic itself, which can significantly reduce the venting requirements and improve part quality. It’s a two-pronged attack on the problem. I always tell my team, "Control what you can, and design for what you can’t."

Source 1: The Air Already in the Mold

This is the most obvious source. Before the cycle starts, the mold cavity is filled with air at normal atmospheric pressure. When you inject molten plastic at high speed—filling the mold in just a few seconds—that an entire cavity’s worth of air needs to be evacuated instantly. If it can’t get out, it gets trapped.

- The Challenge in mold venting: The volume of air is fixed. It’s equal to the volume of your part. The speed of injection determines how fast this air must exit. Faster injection cycles mean you need even more efficient venting to avoid problems.

- The Solution: The primary solution here is mechanical: well-designed vents. These are tiny channels, usually just 0.01 to 0.03 mm deep, that are large enough for air molecules to escape but too small for the thicker molten plastic to flow into.

Source 2: Gases from the Plastic Resin

This source is more complex. Plastic pellets are not just pure polymer. They contain a variety of substances that can turn into gas (volatize) when heated.

- Moisture: This is the most common culprit. Many plastics are "hygroscopic," meaning they absorb moisture from the air. If the pellets are not dried properly before molding, this moisture turns into steam inside the barrel. Steam expands to about 1,700 times its liquid volume, creating a massive amount of gas that needs to be vented.

- Additives and Binders: Colorants, flame retardants, UV stabilizers, and other additives can release gases when subjected to the heat of the injection barrel.

- Resin Degradation: If the plastic is overheated or stays in the barrel for too long, the polymer chains themselves can start to break down, releasing volatile gases.

For my clients, the single biggest improvement they can make here is investing in proper material handling and drying. I had one customer, a company making enclosures for consumer electronics, who was chasing a burn mark issue for weeks. Their mold had adequate venting, so we started looking at their process. It turned out their material dryer wasn’t working correctly. Once they fixed it and started using properly dried resin, the burn marks disappeared. They were trying to solve a mold problem that was actually a material preparation problem. This highlights how everything in the injection molding process is connected.

Common Defects Caused by Poor Mold Venting

Typical Defects that are a result of improper venting of molds.

Injection-molded products are prone to a number of undesirable defects that may occur as a result of poor venting of the mold. These defects do not only harm the outlook, but may also undermine the stability of the object. These defects should be understood in order to enhance the process of molding.

These are typical failures brought about by poor venting:

- Burn Marks: Dark marks on the surface of the product as a result of gas burning inside it.

- Short Shots: The whole mold is not filled and thus portions of the mold will be missing.

- Voids: The holes in the product making it weak.

Such flaws are usually characterized by higher production expenses as well as reduced customer satisfaction. Considering the venting problems at the initial stage is very essential to sustain high quality standards. It is possible to facilitate the minimization of the defect rates and enhancement of the overall product reliability by maximizing the vent design and placement by the manufacturers.

What Are the Telltale Signs of Poor Mold Venting?

As a molder, you need to quickly diagnose production problems to minimize downtime and scrap. But if parts are coming off the line flawed, how do you know poor venting is the reason? Knowing the specific symptoms saves you from barking up the wrong tree, like tweaking machine settings when the real problem actually lies in the mold design. In fact, recognizing these signs is your critical skill as a molder.

The most common indications of poor mold venting are visible defects in the part. These include black or brown burn marks, most especially at the end of the fill path; short shots where the part is incomplete; prominent and weak weld lines; a poor or dull surface finish; even warping or blistering. This happens because the trapped, compressed gas interferes with the ability of plastic to fill the cavity and properly form. Looking at where these defects appear often points directly to a blocked or nonexistent vent.

Learning to read a defective part is like a detective reading a crime scene. The part itself tells you the story of what went wrong during its creation. The location, size, and type of defect are all clues that point toward the root cause. When I’m troubleshooting with a client, the first thing I ask for isn’t their process sheet; it’s a handful of their bad parts. These parts are the best evidence we have.

A Visual Guide to Venting-Related Defects

To help you become a better detective, let’s break down the key signs. I always encourage my clients to create a "defect library" with examples of good and bad parts to train their quality control team.

-

Dieseling (Burn Marks):

- What it looks like: Black or dark brown streaks or spots. They almost look like the plastic has been scorched.

- Where it happens: Almost always at the last point to fill or in deep ribs or corners where air gets trapped.

- The giveaway: If the burn mark is consistently in the same spot on every bad part, you’ve found your problem area. That specific spot is where gas is being compressed with nowhere to escape.

-

Short Shots (Incomplete Fills):

- What it looks like: The part is missing material. The edges might be rounded and incomplete instead of sharp and fully formed.

- Where it happens: Again, usually at the end of the flow path, furthest from the gate.

- How you know it’s venting: If you increase injection pressure and speed but the part still won’t fill completely, it’s likely because of back pressure from trapped gas. The plastic literally can’t fight its way past the air pocket.

-

Weld/Knit Line Issues:

- What it looks like: A visible line, groove, or notch where two plastic flow fronts meet. You might be able to break the part easily along this line.

- Where it happens: Wherever the mold design forces the plastic to split and flow around an obstacle (like a core pin) and meet on the other side.

- The venting connection: While weld lines are normal, poor venting makes them much worse. Trapped gas at the meeting point prevents the two fronts from melting together properly, creating a cold, weak bond instead of a seamless fusion.

Going Beyond the Obvious an Owner’s Perspective

For someone like Michael, who is focused on the bottom line, these defects are more than just cosmetic.

| Defect | Impact on Business Operations |

|---|---|

| Burn Marks | Causes immediate part rejection, increasing scrap rate and material costs. |

| Short Shots | Total waste of machine time and material. Every short shot is a 100% loss. |

| Weak Weld Lines | This is a structural failure waiting to happen. It can lead to product failure in the field, customer complaints, and potentially costly recalls. This is often the most dangerous defect. |

Recognizing these signs early is key. It allows you to pause production and address the root cause—the mold’s venting—rather than producing thousands of defective parts that will eventually end up in the scrap bin.

How Can a Mold Maker Intelligently Design Vents for Optimal Quality?

Yes, it’s one thing to know that poor venting causes defects, but how do we proactively solve it? The customer needs to be assured that the mold maker isn’t just cutting steel, but engineering a tool for a perfect process. Just grinding a few arbitrary slots in the mold isn’t enough. An intelligent approach to venting is a hallmark of a high-quality mold manufacturer.

Accordingly, the vents are designed by an experienced mold maker based on the analysis of plastic flow using Mold Flow simulation software, which predicts where the air will be trapped. Vents are then placed at these "last-to-fill" locations, as well as down the complete parting line. The vent’s depth is critical: it should be shallow enough, for instance 0.015 mm for PS and 0.03 mm for ABS, to allow air to come out but not permit plastic flash. Vented ejector pins and porous mold inserts are also used for areas that are difficult to reach.

This is where true craftsmanship and engineering meet. At CKMOLD, we never treat venting as an afterthought. It’s a fundamental part of our design process from day one. We use simulation to guide our decisions, but we also rely on decades of hands-on experience. A simulation might show you where a vent is needed, but an experienced toolmaker knows exactly how to build and maintain it for long-term production.

The Toolkit for Effective Vent Design

A good mold maker has a variety of techniques at their disposal and knows when to use each one. It’s not a one-size-fits-all solution.

-

1. Parting Line Vents:

- What they are: These are the most common type. A very shallow channel (the "vent depth") is machined across the mold’s parting line for about 5-10 mm, which then opens into a deeper channel (the "exhaust channel") to let the gas escape to the atmosphere.

- Why they are critical: They provide the main escape route for the bulk of the air in the cavity. A continuous vent around the entire perimeter of the part is ideal.

-

2. Vented Ejector/Core Pins:

- What they are: For areas deep inside the mold where air can be trapped (like a tall, narrow rib), standard parting line vents won’t work. The solution is to use special pins that have tiny flats or channels ground along their sides, or are made of a porous material.

- When they are used: Essential for preventing burn marks in deep features, bosses, or any isolated area that will be the last to fill.

-

3. Porous Mold Inserts:

- What they are: For really challenging applications, we can use inserts made of sintered, porous steel. This material is solid but contains a network of microscopic pores. It allows gas to escape right through the steel surface itself, providing 360-degree venting.

- When they are used: Best for high-gloss parts where even the slightest witness line from a vent is unacceptable, or for parts with complex geometries that trap gas in unpredictable ways.

The Science of Vent Depth in mold venting

The single most important parameter in vent design is the depth. It’s a delicate balance.

| Plastic Type | Typical Vent Depth (mm) | Why the Difference? |

|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene (PS) | 0.015 – 0.025 | A very fluid, low-viscosity material that can easily flash if vents are too deep. |

| ABS | 0.025 – 0.040 | A more viscous material that requires a slightly deeper vent to allow gas to escape effectively. |

| Polycarbonate (PC) | 0.040 – 0.060 | A high-viscosity, stiff-flowing material that can handle deeper vents without flashing. |

This is why your mold maker must know exactly what material you will be running. Designing a mold for ABS and then running PS in it is a recipe for disaster—the part will be covered in flash. An intelligent mold maker asks these questions upfront to ensure the design is right from the start.

Injection molding is a very critical process involving mold venting. It is used to make sure that the gases that are trapped in the mold are released. Defects such as burn marks and voids may develop without proper venting. Ventilation systems also play a crucial role in ensuring the quality of indoor air in manufacturing environment. They assist in the regulation of emissions and provision of safe working environment. Adequate ventilation leads to quality products and safety of the workers.

The science of venting of molds is a science of balancing the material and the flow of air. This balance plays a critical role in minimizing the batch of defects and maximizing concurrence in production. High-tech systems and inventions are on-going to enhance venting of molds.

In this paper we examine the science of venting of molds. We talk of the behavior of gases in injection molding and its impact. Ventilation systems, which are effective in manufacturing, are also pointed out.

Understanding this process is one of those "aha!" moments I’ve seen many clients experience. It shifts the focus from just the plastic and the machine to the mold itself as a sophisticated tool. Proper venting isn’t a minor detail; it’s a core principle of good mold design. It ensures the plastic can fill the cavity completely and form a solid, uniform part without fighting against a pocket of compressed air. Let’s dig into why this happens and how to get it right.

What Exactly Is Trapped Gas and Why Does It Ruin Your Parts?

Are mysterious defects continuing to stump you, despite going through all your normal troubleshooting steps? You change your injection parameters, you dry your material to perfection, and the defects persist. It’s very frustrating when you cannot find what is causing this, as time is being wasted along with parts being scrapped. In reality, invisible forces inside your mold are often the cause: trapped gas. It silently destroys your parts, but since you cannot see it, it is almost always the last thing looked at.

Trapped gas is the air and volatile compounds that fail to escape the mold cavity as it’s being filled with molten plastic. This gas becomes cornered and compressed, causing extreme pressure and temperature spikes in localized hotspots. This "diesel effect" burns the plastic, creating black or brown marks. It also creates back pressure that prevents the mold from filling completely – a condition known as short shots – and also results in weak and visible weld lines where plastic fronts meet but fail to fuse properly, creating a structurally compromised part.

To really get to the bottom of this, we need to think about the physics at play. Imagine pushing a plunger into a syringe with your finger over the end. You can only push it so far before the compressed air inside pushes back. Now, imagine that plunger is molten plastic moving at incredible speed, and the trapped air has nowhere to go. The pressure builds up instantly. The temperature of that trapped gas can skyrocket to levels far higher than the plastic’s melt temperature. This is where the real damage begins.

How Does Trapped Gas Cause Defects?

The root of the problem is that gas is compressible, but the molten plastic isn’t. When the plastic flow front traps a pocket of air, it squeezes it into a smaller and smaller space. This rapid compression generates immense heat, often leading to a few key problems:

- Burn Marks (Dieseling): The gas heats up so much it scorches the plastic, leaving black or dark brown residue on the part. This is a telltale sign of a venting issue.

- Incomplete Fill (Short Shots): The back pressure from the trapped gas can be strong enough to physically stop the plastic from filling the furthest points of the cavity.

- Weld Line Weakness: Where two plastic flow fronts meet, they are supposed to fuse. But if a pocket of trapped gas is sitting at that meeting point, it prevents a clean, strong bond from forming.

Why Isn’t This Always Obvious?

The signs aren’t always as clear as a large black scorch mark. Sometimes, poor venting manifests in more subtle ways, which can be even more frustrating for business owners like Michael who rely on consistent quality.

| Subtle Sign | What It Looks Like | Why Venting is the Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Surface Finish | Dull patches or flow marks in areas far from the gate. | Trapped gas disrupts the plastic’s contact with the mold surface, preventing it from perfectly replicating the polished steel. |

| Warpage | The part distorts or bows after ejection from the mold. | Inconsistent filling pressure caused by trapped gas can create internal stresses that are released once the part cools. |

| Inconsistent Part Weight | Parts from the same run have slightly different weights. | This indicates that some cavities are not filling as completely as others, often due to variations in how effectively gas is escaping. |

I once worked with a client who was struggling with a high-gloss part that had persistent dull spots. They blamed the material, the polish, everything but the vents. We took the mold, added a few strategically placed vents in the problem area, and the issue vanished. It was a simple fix, but it required understanding that gas behavior was the true culprit.

Mold Venting Innovations and Technology.

The recent development in venting of molds is changing the manner in which manufacturers approach the removal of gases and the performance of the mould in general. Currently, a number of companies are relying on smarter and more efficient solutions that are not only capable of minimizing defects, but also assist in the delivery of cleaner and more reliable parts. These technologies are simplifying the process of ensuring quality and at the same time production costs remain affordable.

The application of advanced simulation software is one of the largest breakthroughs. The engineers are now able to examine the behavior of trapped air within the mold and manipulate vent designs prior to the production of a single part. Such virtual testing assists in the identification of possible issues early, saves time of development and enhances precision during molding process.

The future of mold venting is also determined by several emerging technologies:

- Smart Sensors: These are used to monitor the performance of the pressure, airflow, and vent in real-time so that the teams can check the performance of parts being molded.

- IoT Connectedness: When systems are connected, manufacturers are able to gather and process data in real-time, which will simplify the process of optimizing processes and maintaining standardized production.

- Better Materials: More durable and advanced materials are currently being employed in making longer lasting vents that are more efficient in harsh conditions.

Combined, these advances provide manufacturers with some of the potent means of enhancing reliability, scrap reduction and overall productivity. One way through which companies can remain competitive in such a highly developed manufacturing business is to keep up with new developments in the technology of mold venting.

Conclusion

We’ve discussed everything from what the trapped gas is and where it originates, to the defects it creates, and how a good mold maker engineers a solution. Proper venting is not a minor feature; it’s fundamental to the injection molding process. It is the science of making space for plastic by efficiently removing gas and ensuring high-quality consistent parts. Neglecting it leads directly to scrap, downtime, and unreliable products, which will affect your bottom line.