Are your injection molded parts coming out with frustrating defects like warpage, ugly marks, or inconsistent finishes? This often leads to wasted material, project delays, and unhappy clients, making you feel like you’re just guessing at the machine settings. The secret to consistent, high-quality parts isn’t just the plastic itself; it’s about mastering the mold temperature for that specific material. It’s one of the most critical variables in the entire process.

The right mold temperature is crucial because each plastic has a unique thermal profile that dictates how it flows, cools, and solidifies. Getting it right ensures proper part formation, excellent surface finish, and stable dimensions. The wrong temperature can cause a host of defects, from visible flaws like sink marks and weld lines to hidden problems like high internal stress. This directly compromises the look, strength, and overall quality of your final product, impacting both production efficiency and your bottom line.

You might think a few degrees here or there don’t make a huge difference. But in my years on the factory floor and running my own business, I’ve seen how a small temperature mistake can turn a profitable job into a costly failure. The relationship between the material, the mold, and the temperature is a delicate dance. When you get the steps right, the results are flawless. When you get them wrong, you end up stepping on your own toes.

Let’s dive deeper into why this matters so much and how you can get it right every time.

What Happens if Your Mold Temperature is Wrong?

Have you ever pulled a part from the mold that looked perfect, only to find it cracks under a little bit of pressure later on? This hidden weakness, often caused by high internal stress, can lead to field failures and damage your company’s reputation. It’s a silent killer in manufacturing. Understanding the direct consequences of an incorrect mold temperature is the first step to preventing these costly and embarrassing mistakes from ever happening.

If your mold temperature is too low, you risk poor plastic flow, which leads to short shots, prominent weld lines, and a dull, low-quality surface finish. The part will also be packed with high internal stress, making it brittle. Conversely, if the temperature is too high, the cycle time increases dramatically, parts can stick to the mold, and you might see defects like flash or warping as the part cools unevenly. Finding that "just right" temperature is the key.

Over my career, I’ve seen both extremes, and neither is good for business. A client like Michael, who values quality and efficiency, needs to avoid these pitfalls. Let’s break down exactly what you’re up against when the temperature isn’t dialed in correctly.

The Dangers of a Mold That’s Too Cold

When the mold is too cold for the specific plastic you’re using, the molten material cools down too quickly as it enters the cavity. Think of it like trying to spread cold butter—it doesn’t flow smoothly. This causes several major problems:

- Short Shots: The plastic solidifies before it can completely fill the mold cavity, resulting in an incomplete part.

- Weld Lines: Where two or more plastic flows meet, they are too cold to meld together properly, creating a visible and weak line.

- Poor Surface Finish: The plastic freezes against the mold wall instantly, perfectly replicating any microscopic imperfections and resulting in a dull or "cloudy" appearance instead of a clean, glossy finish.

- High Internal Stress: The molecules are frozen in a stressed, unnatural state. The part might look fine coming out of the machine, but it will be brittle and prone to cracking or warping over time.

The Problems with a Mold That’s Too Hot

You might think that running the mold hotter is a safe bet to avoid the problems above, but it comes with its own set of challenges that directly impact your bottom line:

- Extended Cycle Times: The biggest issue is cooling. The part needs more time to cool down and become stable enough for ejection. Every extra second of cooling time is money lost in a high-volume production run.

- Sticking Parts: A hot part can be softer and may stick to the mold, causing issues with ejection and potentially damaging the part or the mold itself.

- Flash: The plastic stays molten for longer, increasing the chance it will seep into tiny gaps in the mold, such as the parting line, creating excess material (flash) that needs to be trimmed.

- Warping and Sink Marks: While a cold mold can cause stress, a very hot mold can lead to uneven cooling, which also causes warping. It can also worsen sink marks in thick sections as the material continues to shrink.

How Do Temperature Needs Differ for Amorphous and Semi-Crystalline Plastics?

Do you treat all plastics the same when you’re setting up a new injection molding job? It’s a common oversight that leads to wildly inconsistent results. A temperature setting that works perfectly for a material like ABS could be a complete disaster for Nylon. You end up fighting the material’s fundamental nature. The solution lies in understanding the two main families of plastics—amorphous and semi-crystalline—and their different thermal needs.

Amorphous plastics, like ABS and Polycarbonate (PC), have a random molecular structure and a wide softening range. They need a mold temperature set below their heat deflection temperature to solidify properly and quickly. In contrast, semi-crystalline plastics, like Polypropylene (PP) and Nylon (PA), have an ordered, crystalline structure and a sharp melting point. They require a higher mold temperature to allow these crystal structures to form correctly, which is what gives them their superior strength and chemical resistance.

Getting this distinction right is fundamental. It’s like knowing whether you’re building with bricks or pouring concrete; the process and requirements are completely different. Once you grasp this concept, setting your process parameters becomes much more logical and predictable.

Working with Amorphous Plastics (e.g., PC, ABS, PS)

Amorphous plastics have a jumbled, spaghetti-like molecular structure. They don’t have a true melting point; instead, they have a "glass transition temperature" (Tg), where they go from a hard, glassy state to a soft, rubbery one. When molding these materials, the goal is to cool the plastic down below this Tg so it becomes rigid enough to eject. The mold temperature is critical for controlling viscosity, reducing internal stress, and achieving a good surface finish. Because they shrink less and more predictably than their crystalline cousins, they are often chosen for high-precision applications.

Mastering Semi-Crystalline Plastics (e.g., PP, PE, PA, POM)

Semi-crystalline plastics are different. They have regions where the polymer chains are neatly folded into ordered, crystalline structures. These structures are what give them their toughness, wear resistance, and chemical resistance. They have a sharp, defined melting point (Tm). The key to processing these materials is giving them enough time and heat in the mold to form these crystals. If the mold is too cold, the material "quenches" before crystallization is complete. The resulting part will be weak, brittle, and dimensionally unstable. Therefore, the mold temperature must be kept relatively high, often just below the crystallization temperature, to ensure the part achieves its intended properties.

Here is a simple table to show the main differences:

| Feature | Amorphous Plastics | Semi-Crystalline Plastics |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Structure | Random, jumbled, like tangled spaghetti | Ordered crystalline regions mixed with amorphous regions |

| Melting Behavior | Softens gradually over a wide temperature range (Tg) | Has a sharp, distinct melting point (Tm) |

| Shrinkage | Lower and more uniform | Higher and more differential (different rates in flow and cross-flow directions) |

| Typical Mold Temp. | Generally lower, focused on setting the part shape | Generally higher, needed to control the rate of crystallization |

| Common Examples | PC, ABS, PS, PMMA | PP, PE, PA (Nylon), POM (Acetal), PBT |

What Are the Ideal Mold Temperatures for Common Plastics like ABS, PC, and PP?

When you look up the right mold temperature for a specific plastic, you often find a frustratingly large range of numbers. Picking a value at the low end of that range versus the high end can completely change the outcome of your part. You need more than just a number; you need context for why that number works. I’m going to share the specific temperature ranges I’ve found to be most effective for some of the most common materials we work with every day.

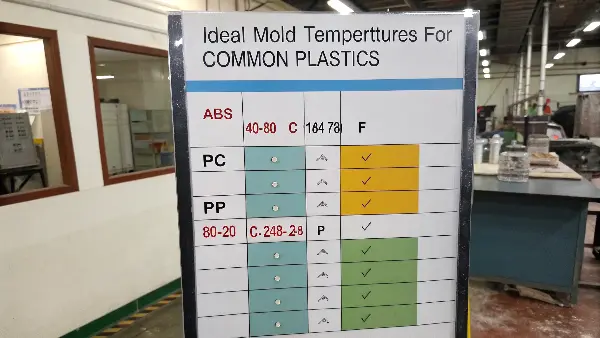

While a material’s technical data sheet is always your primary guide, having reliable starting points is essential. For general-purpose ABS, a mold temperature of 40-80°C (104-176°F) balances good flow with a quality finish. For Polycarbonate (PC), you need a much hotter mold, typically 80-120°C (176-248°F), to minimize internal stress and achieve good clarity. For Polypropylene (PP), a semi-crystalline material, a range of 30-70°C (86-158°F) works well, with the higher end improving stiffness and stability.

These aren’t just random numbers. They are based on the fundamental nature of each polymer. As a business owner, knowing these ranges helps you have intelligent conversations with your production team and suppliers. It empowers you to spot potential issues before they become expensive problems. Let’s look at a few key materials in more detail.

A Quick Reference Guide

This table provides a good starting point for some of the most frequently used plastics in the industry. Always remember to cross-reference with your specific material grade’s data sheet, as additives and fillers can alter these recommendations.

| Material | Type | Typical Mold Temp. (°C) | Typical Mold Temp. (°F) | Key Considerations & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABS | Amorphous | 40 – 80°C | 104 – 176°F | Higher end of the range improves gloss and surface finish. |

| PC | Amorphous | 80 – 120°C | 176 – 248°F | Critical for reducing internal stress and preventing brittleness. Required for optical parts. |

| PP | Semi-Crystalline | 30 – 70°C | 86 – 158°F | Higher temps improve crystallinity, leading to better stiffness and dimensional stability. |

| PA66 (Nylon) | Semi-Crystalline | 70 – 100°C | 158 – 212°F | Mold temperature is crucial for achieving proper crystallization and mechanical properties. |

| POM (Acetal) | Semi-Crystalline | 80 – 105°C | 176 – 221°F | A hot mold is essential for a good crystalline structure, ensuring low friction and high strength. |

| HDPE | Semi-Crystalline | 30 – 70°C | 86 – 158°F | Influences shrinkage and warpage; higher temperatures can improve surface appearance. |

| PS (Polystyrene) | Amorphous | 10 – 70°C | 50 – 158°F | A colder mold is often sufficient, helping to keep cycle times short for disposable items. |

Choosing a temperature within these ranges depends on the specific part geometry. A thin-walled part might require a hotter mold to ensure it fills completely, while a thick-walled part might use a cooler mold to speed up the cycle time, as long as sink marks are not an issue.

How Can You Balance Cycle Time and Part Quality Through Temperature Control?

Your customers want parts delivered yesterday, but your production team says that speeding up the cycle time is hurting part quality. This classic conflict between speed and quality can feel like a no-win situation. Pushing too hard for one often means sacrificing the other, which ultimately hurts either your profits or your reputation. The solution isn’t just about raw speed; it’s about efficiency. And mold temperature is your primary lever for optimizing this balance.

Balancing cycle time and quality involves a methodical search for the "sweet spot" mold temperature. You should begin with the material supplier’s recommended temperature to establish a baseline of good quality. From there, you can try lowering the temperature in small increments (e.g., 3-5°C) while also shortening the cooling time slightly. Carefully inspect the parts at each step for any new defects. This iterative process helps you find the lowest possible temperature and shortest cycle time that still meets all quality specifications.

This optimization process is where operational excellence really shines. It’s not about taking shortcuts; it’s about scientifically finding the most efficient process window. I’ve helped many clients, including those with pressures just like Michael faces, walk through this process to unlock hidden capacity in their operations.

The True Cost of a Hot Mold

The main drawback of a hot mold is its direct impact on cooling time, which is often the largest portion of the total injection molding cycle. A hotter mold means the plastic part needs more time to cool down and become solid enough to be ejected without deforming. Let’s use a simple example. If you have a 30-second cycle time and raising the mold temperature by 10°C adds 4 seconds of cooling, you’ve just increased your cycle time by over 13%. Over a run of 100,000 parts, that’s a significant loss of production capacity and profit. It’s a direct, measurable cost.

The Hidden Price of a Cold Mold

On the flip side, running the mold too cold in a chase for a shorter cycle time can be even more costly. The cost of a rejected part isn’t just the wasted material and machine time. It’s the labor cost of sorting good parts from bad, the energy consumed to produce a scrap part, and the potential for a bad part to slip through to the customer. Saving 4 seconds on the cycle is completely worthless if your reject rate jumps from 1% to 15%. A single customer return due to a brittle, stress-cracked part can wipe out the savings from an entire production run.

A Practical Optimization Strategy

So how do you find the perfect balance? Follow these steps:

- Establish a Baseline: Start your process using the mid-to-high range of the material data sheet’s recommended mold temperature. Run the machine until the process is stable and produce a batch of parts.

- Qualify the Parts: Thoroughly inspect these baseline parts. Check their dimensions, look for visual defects (sinks, weld lines, gloss), and if necessary, perform mechanical tests to check for strength and brittleness. These are your "golden parts."

- Begin Optimization: If the quality is excellent, lower the mold temperature by 3-5°C. At the same time, you can try to reduce the cooling time by a small amount (e.g., 0.5-1.0 seconds).

- Inspect and Repeat: Produce another small batch and inspect them with the same rigor. Are they still identical to your golden parts? If yes, repeat step 3.

- Find the Limit: Continue this process until you see the first sign of a quality issue—maybe a slight haze on the surface, a more prominent weld line, or a dimension that is drifting out of spec.

- Set the Process: Once you find that limit, increase the temperature back to the last setting that produced perfect parts. This is your optimized process window—the fastest possible cycle time that guarantees consistent, high-quality parts.

Conclusion

In injection molding, controlling the mold temperature is not just a technical detail; it’s a core business strategy. The right temperature, specific to each material, is the key to achieving excellent part quality, from surface finish to mechanical strength. It’s the critical factor that allows you to balance the competing demands of high quality and short cycle times. Understanding this principle directly impacts your efficiency, reduces waste, and ultimately protects your bottom line.